site search

online catalog

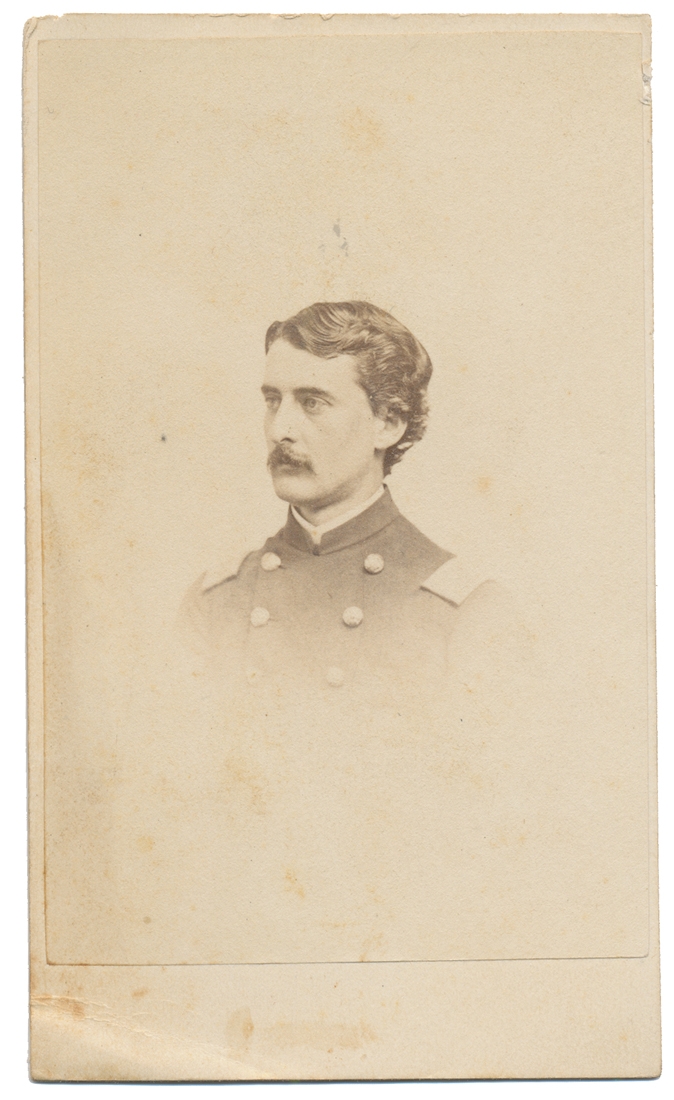

CDV BUST VIEW OF ADJUTANT, LATER LT. COLONEL, THOMAS SHERWIN, JR., 22ND MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY – WOUNDED IN ACTION AT GAINES’ MILL, VA – BREVET BRIG. GENERAL FOR DISTINGUISHED GALLANTRY AT GETTYSBURG

$200.00 SOLD

Quantity Available: None

Item Code: 2020-495

Bust view of Sherwin wearing a double breasted frock coat with shoulder boards visible. CDV is in very good condition with very minor soiling, a slight crease at the lower left of the mount, and very minor edge wear. BM: Whipple, Boston.

Born in Boston in 1839, Sherwin was a 22 year old Harvard graduate employed as a schoolteacher residing in Dedham, MA when he enlisted on 10/1/61 as a 1st Lieutenant. On 10/8/61 he was mustered into Field & Staff, 22nd Massachusetts Infantry. Promoted to Adjutant on 10/1/61 and to Major on 6/28/62. Wounded on 6/27/62 at Gaines’ Mill, VA. Promoted to Lt. Colonel 10/17/62, Colonel by Brevet on 9/30/64. On April 3, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Sherwin for the award of the honorary grade of brevet brigadier general, United States Volunteers, to rank from March 13, 1865, for distinguished gallantry at the Battle of Gettysburg and for gallant and meritorious services during the war. Sherwin mustered out on 10/17/64 at Boston.

By June 1863, when the 22nd Massachusetts marched northward along with the Army of the Potomac in pursuit of Lee’s invading army, the regiment had been severely whittled down due to casualties and disease. At Gettysburg they took just 137 men into action, making it the smallest Massachusetts infantry regiment on the field during the battle.

Lt. Col Sherwin was in command of the 22nd Mass. during the Gettysburg Campaign. He had assumed command of the regiment just after Chancellorsville, only two months prior, when Col. William S. Tilton was promoted to brigade command. The 22nd Massachusetts would therefore fight at Gettysburg under a brigadier and regimental commander who were new to their positions.

When the Battle of Gettysburg began on July 1, 1863, the V Corps was still about 20 miles away in Maryland. The 22nd Massachusetts had camped the previous evening at Union Mills, Maryland near the Pennsylvania border. At 1 a.m. on July 1, they were roused and made a hard march of 10 miles to Hanover, Pennsylvania which they reached in mid-afternoon. After a short rest, they pressed westward to Gettysburg and marched through most of the night, pausing for a bit of sleep roughly between 2 and 5 a.m. on July 2. They marched the final miles to Gettysburg during the morning of July 2, arriving about noon at Wolf Hill, south of the Hanover Road and well behind the center of the Union line. Here the men collapsed and got a few hours sleep while the generals tried to decide where to deploy the V Corps.

When General Daniel Sickles advanced his III Corps to the Peach Orchard and Emmitsburg Road, it soon became apparent that the Union left flank was stretched awfully thin. The V Corps was therefore ordered to the left flank. At about 4:30, with the Confederate assault on the Peach Orchard already underway, the 22nd Massachusetts packed up and marched with their division towards the fight. The division was commanded by General James Barnes, another Bay Stater, formerly in command of the 18th Massachusetts, and also new to his role. Barnes sent Strong’s brigade (including the 20th Maine) off to the far left to hold Little Round Top while his other two brigades, Tilton’s and Sweitzer’s, marched past the Wheatfield, turned to the left, and took up a position on a wooded knoll strewn with boulders known as Stony Hill..

The men of the 22nd Massachusetts settled in among the trees and rocks, making small piles of cartridges and caps on the ground where they knelt to facilitate loading. It seemed a good spot and they expected to hold it for some time. “We had marched too far and borne too much,” wrote James Parker, the regimental historian, “to be pushed over the ridge behind us.” From that rise, they had a commanding view of Rose’s farm. Immediately before them, the ground sloped downward into a shallow swale. The farmhouse itself stood directly to their front, about 250 yards away. As it would happen, they would not be there for long.

As soon as Tilton’s Brigade took their position on Stony Hill, Kershaw’s Brigade of South Carolinians attacked. The 22nd Massachusetts opened fire and their brigade managed to stop the advance. But the South Carolinians regrouped and came on again. “So much din and smoke, yelling and cheering…if any man had sensations of fear before or while going in, he had no time or opportunity for such thoughts now,” Parker later wrote.

The South Carolinians pressed the attack and shifted to their left, circling around the exposed right flank of Tilton’s brigade. On that end, the 118th Pennsylvania had refused the flank, bending their line back upon itself. This strengthened their position but also widened the gap in the Federal line through which South Carolinians were now pouring.

Watching this evolve, Tilton was becoming unnerved. He sent word back to Barnes that he was being flanked. An order came back from Barnes, “Fall back in good order if unable to hold the position.” Sweitzer was given the same order. Unfortunately, Barnes had absolutely no permission to make this withdrawal. He had not consulted General Sykes, in command of the V Corps, nor did he alert Colonel de Trobriand (commanding a brigade of the III Corps) whom Barnes had been ordered to support. De Trobriand saw Tilton’s men moving off to the right and rear and rode up to the nearest officer, immediately asking where they were going. The response: “We do not know.” De Trobriand demanded to know who had given the order to withdraw. The response: “We do not know.” Furious, de Trobriand was forced to withdraw his brigade as well. The Federal position on and around Stony Hill fell apart.

Tilton, in his official report, states that his regimental commanders, having already repulsed two charges, were loathe to leave the position and even wanted to advance. The latter would have been suicide. But, given their strong position, we can imagine Lt. Col. Sherwin and the 22nd Massachusetts felt they could hold a good deal longer.

As the men of the 22nd Massachusetts continued firing, the word passed down their line, “We are flanked! Change front!” Somewhat stunned, they rose up, “coolly picked up their cartridges and caps, carried all wounded and even their guns to the rear.” The withdrawal of Barnes’s brigades was not a rout, but was certainly confused. As they fell back towards Trostle’s Woods, the 22nd Massachusetts was, at times, mingled with other regiments. Periodically, they halted to reform, keeping their eyes on their colors. As they withdrew, other brigades streamed forward in an attempt to fill the gap Barnes had just created. They would be pushed back as well.

At one point during the withdrawal, Lt. Col. Sherwin fell to his knees, doubled over. Men rushed to his aid and found that a bullet had passed through his uniform, and the shock of it had knocked him down.

The 22nd Massachusetts took up a position along a stonewall in Trostle’s Woods, south of the Trostle House. There they slept on their arms. On the morning of July 3, the 22nd Massachusetts, along with their brigade, was deployed further towards the left flank, occupying the saddle between the Round Tops. Taking cover behind the many boulders there, they exchanged fire with Confederates who occupied Devil’s Den. “Under almost perfect cover,” Parker wrote, “they became so persistently annoying and dangerous that we could not even show a finger.”

Pickett’s Charge took place far from their position. As the battle drew to a close, the Confederates in Devil’s Den were finally driven out by another division and the 22nd Massachusetts saw that their rivals were, “the raggedest, most insignificant and dirty crowd of rebels we had ever seen.” By the close of the battle, the 22nd Massachusetts had suffered casualties of 15 killed and 25 wounded (or roughly 30%). [Information on Sherwin’s actions at Gettysburg obtained from the blog historicaldigressons.com.]

Following the war, Sherwin was a member of GAR Post #144 in Dedham, MA. He died on 12/19/1914 in Boston. He is buried in Old Village Cemetery in Dedham, MA; the inscription on his gravestone reads, “A gallant officer / in the war for the Union / A public spirited citizen / An upright man”. At the time of his death, he was chairman of the board of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company. [photos of grave marker and obit taken from findagrave.com]. [ld]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS,

CLICK ON ‘CONTACT US’ AT THE TOP OF ANY PAGE ON THE SITE,

THEN ON ‘LAYAWAY POLICY’.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About CDV BUST VIEW OF ADJUTANT, LATER LT. COLONEL, THOMAS SHERWIN, JR., 22ND MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY – WOUNDED IN ACTION AT GAINES’ MILL, VA – BREVET BRIG. GENERAL FOR DISTINGUISHED GALLANTRY AT GETTYSBURG

For inquiries, please email us at [email protected]

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Cavalry Carbine Sling Swivel »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

featured item

AMBROTYPE OF IDENTIFIED MUSICIAN OF THE PETERSBURG MILITIA

Formerly in the collection of Bill Turner, this sixth plate ambrotype has a great pedigree, having been published as Figure 2 in Albaugh’s landmark “Confederate Faces.” Identified there as a, “Musician named Crowder, of Petersburg, Va., in… (1138-1866). Learn More »