site search

online catalog

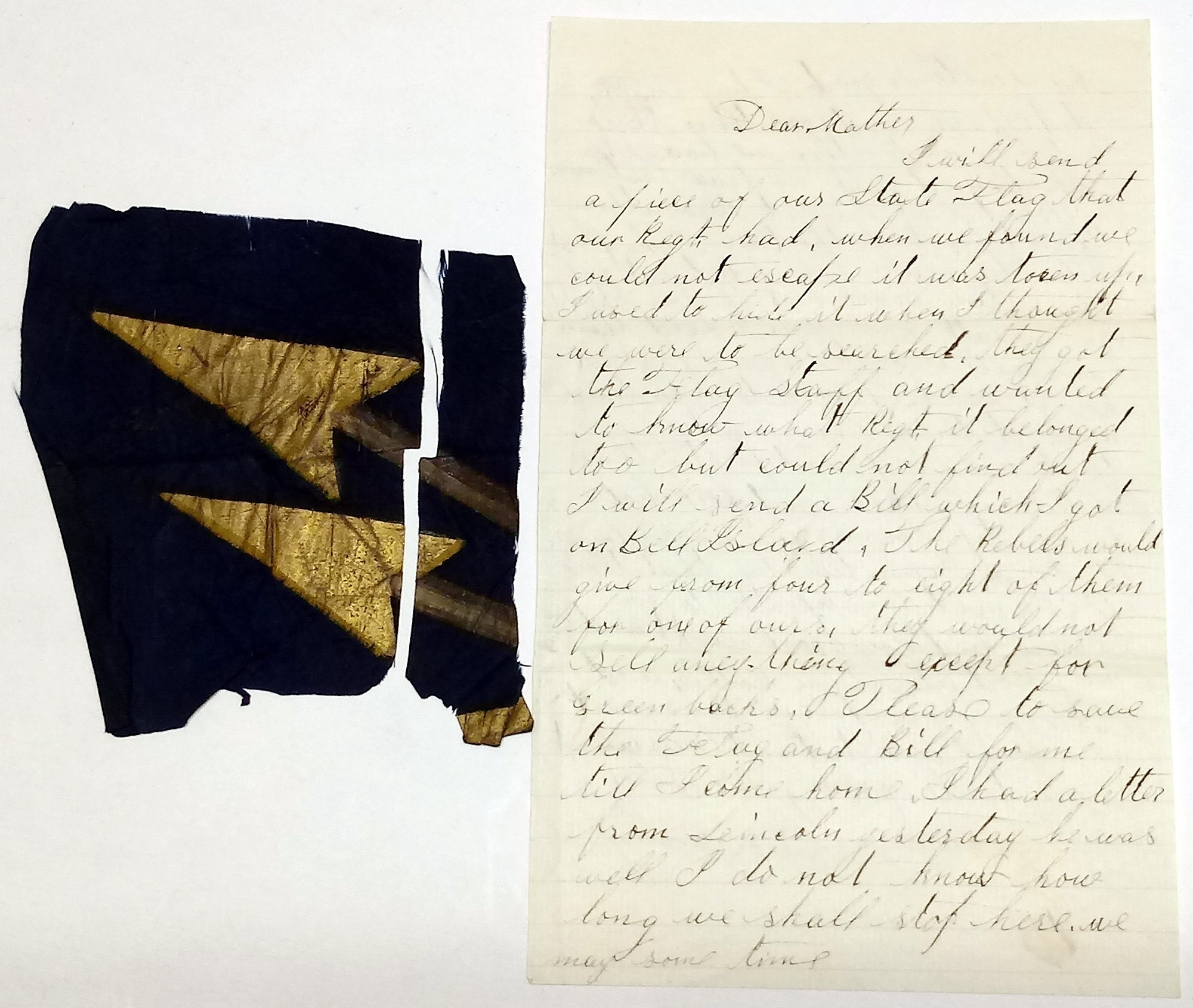

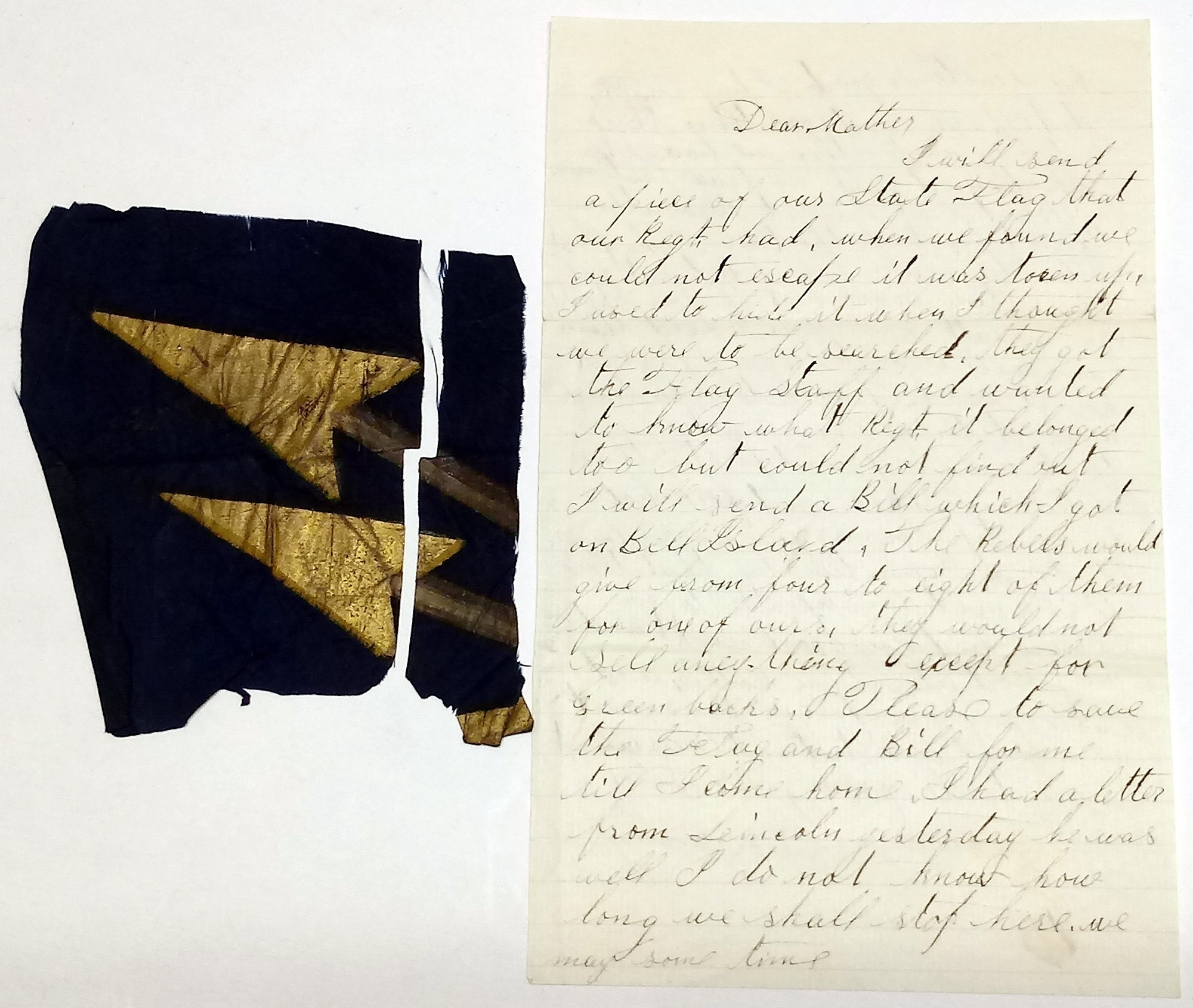

PIECE OF THE FLAG OF THE 16th MAINE TORN UP TO AVOID CAPTURE ON JULY 1, 1863, AT GETTYSBURG WITH LETTER FROM SERGT. DEARING SENDING IT HOME

Hover to zoom

$2,250.00 SOLD

Quantity Available: None

Item Code: 766-1082

“The intrepid color bearers, Mower and Thomas, waved defiance to the foe, as they closed around the regiment. Although conspicuous marks, they gallantly held aloft the loved emblems until capture was inevitable, and then by advice and consent of the colonel and other officers, broke the staff and tore in shreds the silk banners, the pride of the regiment, and divided the pieces. Today away down in Maine, can be found in albums and frames, gold stars and shreds of silk — cherished mementos of the critical period.” –Abner Small, 16th Maine

On July 1, 1863, the 16th Maine fought with Robinson’s Division of the First Corps for some three hours along Oak Ridge against Confederate attacks from the west and from the north. Indeed, as regiments on the right of the line swung back, the 16th Maine found itself at the apex of the line. When the Eleventh Corps collapsed on the right the rest of the division was pulled back, but the 16th Maine was ordered to advance on its own to hill overlooking the Mummasburg Road and fight a delaying action to buy time. When they finally withdrew their own retreat had been cut off and most of the survivors were captured near the railroad cut.

As Abner Small recalled in the regimental history, rather than surrender the colors, they were torn up and divided among the men as Confederates closed in. This is one of those mementos, preserved in the effects of Charles Dearing, Co. B 16th Maine. Several others are known in public and private collections. This is one of the more substantial, measuring 4 inches square and showing two gilt arrowheads, recognizable painted motifs from one of the flags.

Dearing served with the regiment throughout the war, mustering in with it in August 1862 and out in June 1865. He rose from corporal to regimental quartermaster sergeant. At Gettysburg he was first (or orderly) sergeant of Company B. The fragment comes with the letter in which he sent it home to his mother and in which he details its capture.

“Dear Mother,

I will send a piece of our State Flag that our Regt had. when we found we could not escape it was toren up. I used to hide it when I thought we were to be searched. They got the Flag staff and wanted to know what Regt it belonged too but could not find out I will send a Bill which I got on Bell Island. The Rebels would give from four to eight of them for one ours. they would not sell any thing except for Green backs. Please to save the Flag and Bill for me till I come home...”

Dearing likely wrote the letter and sent the piece home from “Camp Parole” at Annapolis, where he spent several months awaiting exchange after thirteen weeks in Confederate prison camps. The rest of the letter assures her that he is improving in health and gives some details of life in camp, his purchase of a cooking skillet (a “Spider,”) etc., and indicates he still has “courage” enough to serve out his remaining two years in the army. (Dearing was exchanged in late May 1864 and returned to the regiment to see action in Grant’s Petersburg Campaign, and was promoted to quartermaster sergeant in December 1864.) He likely sent it home in October or November. Interestingly, he may have sent home another fragment of the flag as well, which is mentioned in a letter written to him on Nov. 26, 1863, by family members gathered at their old homestead in Webster, Maine.

The flag fragment shows two gilt arrowheads on either side. It has a tear down the middle, but there is no missing material at the join and it does not affect their presentation. Dearing refers to it as coming from their “State Flag,” and some other sources refer to one of the flags as the “state colors,” which has sometimes led to its identification as a flag bearing the state seal. It seems clear from other extant fragments in public and private collections, however, and especially from this one, that it was the blue regimental flag bearing the “Arms of the United States,” that is: an eagle with arrows and olive branch in its talons, an arc of stars in two rows overhead, with a ribbon scroll underneath bearing the regimental designation. Calling it the state flag likely derived from the appearance of the state name on the ribbon or perhaps because it might have been presented by the state. (We know that of the replacement stand of colors they received in November 1863, one was from the state and another from a private group.)

This would look great framed with the letter. It is a wonderful relic of a fighting regiment, with a great provenance and documentation, treasured by one of the soldiers on the field that day, a memento of a gallant action in the war’s most famous battle. [sr]

GENEALOGICAL NOTES

Charles Edwin Dearing was born 30 October 1838 in Webster, Maine, one of eight children born to John (b. ca. 1798) and Caroline Perry Dearing 9 (b. 1806.) John was a stage driver. The union produced 8 children: Joseph H. (born ca. 1832, ) George G. 1834,) Albert Lincoln (ca. 1836,) Charles E. (1838,) John F. (ca. 1840,) Susan E. (ca. 1842,) Laura S. (ca. 1845,) and Bradford P. (ca. 1848.)

John Dearing (Sr.) died 27 September 1847 and the family thereafter is found listed in household of son Joseph H. Dearing in Webster, listed as a farmer. George is not listed in the household in 1850 and presumably is on his own by then. The farm may have been the family homestead, inherited by Joseph as eldest son. George shows up in 1863 in Thanksgiving letter to Charles, a reference in Albert’s (Lincoln’s) letter to Charles, and in reports of Caroline’s 1863 remarriage at “the home of her son George.”

At age ten (about 1848) Charles was sent to Gardiner, ME, to live with his maternal uncle Joseph Perry, a machinist, and train in that profession. In the 1850 census he is listed both in Webster (in the Perry household) and in Gardiner. “After attaining his majority,” presumably ca. 1856, Charles moved to Boston, but returned to Gardiner to manage his uncle’s machine shop and is there by the time of the 1860 census. He is listed in Webster in Joseph’s household, but also seems to have had lodging in Gardiner, where appears as machinist, age 22, in the household of Henry Foy.

By 1860 Joseph had married (Susan V. Dearing) and had one son (John L. Dearing.) Albert L. had served briefly in the U.S. Army, but had been discharged and was again at home. George is on his own. John F. is not listed. Some secondary sources indicate he died 5 October 1858. An 1863 Thanksgiving letter to Charles from the family indicates two family members were absent: Charles and another male member of the family who had died (John L., son of Joseph H., was still alive in 1870.)

Caroline Perry Dearing remarried in April 1863. Her second husband was Willis Sprague, a deacon, one-time state senator, and resident of Topsham. The family’s 1863 letter to Charles referring to “Father” must mean Sprague. The letter is being written from the “old homestead” in Gardiner and Caroline is referred to as “a visitor.” Willis Sprague dies in 1867 or 1869 and by the 1870 census Caroline is once again in the household of Joseph H. in Gardiner. She dies in 1882 at age 76.

Albert Lincoln Dearing served in the 5th Maine, reaching the rank of Captain. He was seriously wounded at Second Fredericksburg (Sedgwick’s attack during the Chancellorsville campaign,) and discharged in 9/8/1863.

CHARLES E. DEARING SERVICE NOTES

Charles E. Dearing was a machinist when he enlisted 26 July 1862 at age 24 and mustered into Co. B 16th Maine on 14 August 1862 as a corporal. The regiment moved to Washington and in October was assigned to the First Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

Dearing is recorded as promoted from corporal to fifth sergeant as of 1 January 1863, likely in the wake of the regiment’s losses at Fredericksburg. They had been heavily engaged on the Union left, where Federal attacks had some initial success, and Dearing himself was struck by a spent ball that pierced his cap box and belt, but lodged in his clothing. He was promoted again, to company first sergeant to date March 15, 1863.

On July 1, as part of Robinson’s Division of the First Corps, the 16th Maine was deployed with the rest of Paul’s brigade to reinforce Baxter’s brigade along Oak Ridge (the two brigades constituting Robinson’s division.) After three hours of fighting against Confederate attacks from the west and north, the collapse of the Eleventh Corps opened them up to attacks from the northeast as well. The regiment had found itself at the apex of Robinson’s line as regiments to its right bent back to face north, and they were now ordered to advance to a hill commanding the Mummasburg Road and buy the division time to withdraw. By the time they themselves pulled back their retreat had been cut off and the survivors were compelled to surrender near the railroad cut. The battlefield monument records that of 275 engaged 11 were killed, 63 wounded, and 159 were captured. Their proportional loss may have been higher: their official report says only 248 entered the fight. As Confederates pressed in to gather prisoners, the men tore apart the regiment’s colors rather than surrender them. Shreds and fragments were concealed on their persons and later sent home as mementos. One of these exists in Dearing’s effects, along with an undated letter sending it to his mother. He seems to have sent two to family members: a reference by a sister-in-law in the family’s Thanksgiving 1863 letter to Charles indicates she had received a piece, so he likely sent both pieces to the family before November 26 and after September 29, 1863.

Dearing chronicled his battle experience and thirteen weeks in captivity in a letter home to his mother. He was marched south to Staunton, VA, from July 4 to July 18, and sent from there to Richmond by train. He reached Richmond on July 20, spent some time in Tobacco Warehouse (“opposite Castle Thunder,”) and was then transferred to Belle Isle. He was released on parole at City Point on September 29 and was sent to Camp Parole at Annapolis to await exchange. He received a 30-day furlough home from April 15 to May 15, 1864. His diary chronicles his trip from Maine starting May 12 and mentons receiving news he had been exchanged. At Camp Parole he was placed in charge of a company formed of men heading back to their regiments. This was designated “1st Company 3rd Battalion.” Reaching Washington and crossing into Virginia, Dearing (and presumably the rest of the company) received arms and equipment at a point of “Distribution” and then marched to rejoin the army at the front. Dearing rejoined the 16th Maine on June 6.

During his absence the First Corps had been dissolved and the regiment transferred to the Fifth Corps, which was heavily involved the fighting of Grant’s Overland Campaign against Richmond. They had fought and taken losses at Wilderness and Spottsylvania. He was there in time for Cold Harbor in June, and the first fighting at Petersburg. In August he was with them in the fighting at the Weldon Railroad and was reportedly briefly captured before escaping back to the regiment. He was promoted to regimental Quartermaster Sergeant 12/14/64. The regiment saw further action during the siege of Petersburg, Hatcher’s Run, the Weldon Railroad again and at Five Forks.

Dearing was discharged with the regiment at Arlington Heights June 5, 1865, and returned home to manage his uncle’s machine shop again. They were eventually partners in the operation, but in 1887 Dearing turned to agriculture for health reasons and moved to Farmingdale. He served in several civic posts in Gardiner and Farmingdale, and was a charter member of Heath Post G.A.R. In 1869 he married Emily White (1844-1920.) They had three children, two of whom survived to adulthood. Emily died in 1920. Charles died in 1930 at age 91.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS,

CLICK ON ‘CONTACT US’ AT THE TOP OF ANY PAGE ON THE SITE,

THEN ON ‘LAYAWAY POLICY’.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About PIECE OF THE FLAG OF THE 16th MAINE TORN UP TO AVOID CAPTURE ON JULY 1, 1863, AT GETTYSBURG WITH LETTER FROM SERGT. DEARING SENDING IT HOME

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Selection Of Unframed Prints By Don Troiani »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

Large English Bowie Knife With Sheath 1870’S – 1880’S »

Imported (Clauberg) Us Model 1860 Light Cavalry Officer's Saber »

featured item

EXTREMELY RARE COLONIAL AMERICAN MADE "PIERCED HEAD WEEPING HEART" HALBERD

Perhaps the most desired artifacts of the French and Indian War and the early days of the American Revolution are the polearms. The two patterns most sought by experts and collectors are of the "Pierced Dagger" and "Weeping Heart" designs. These rare… (1298-01). Learn More »