site search

online catalog

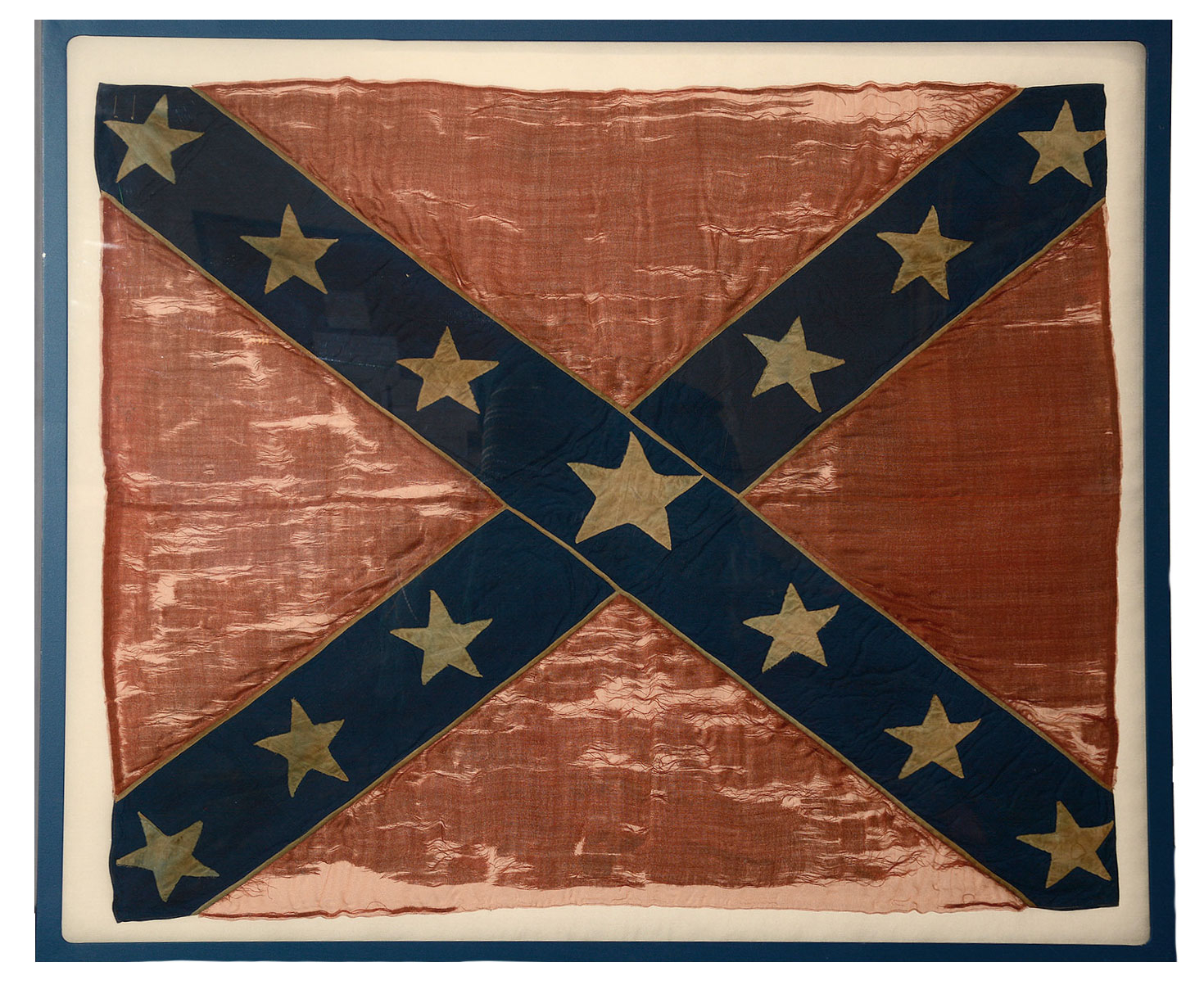

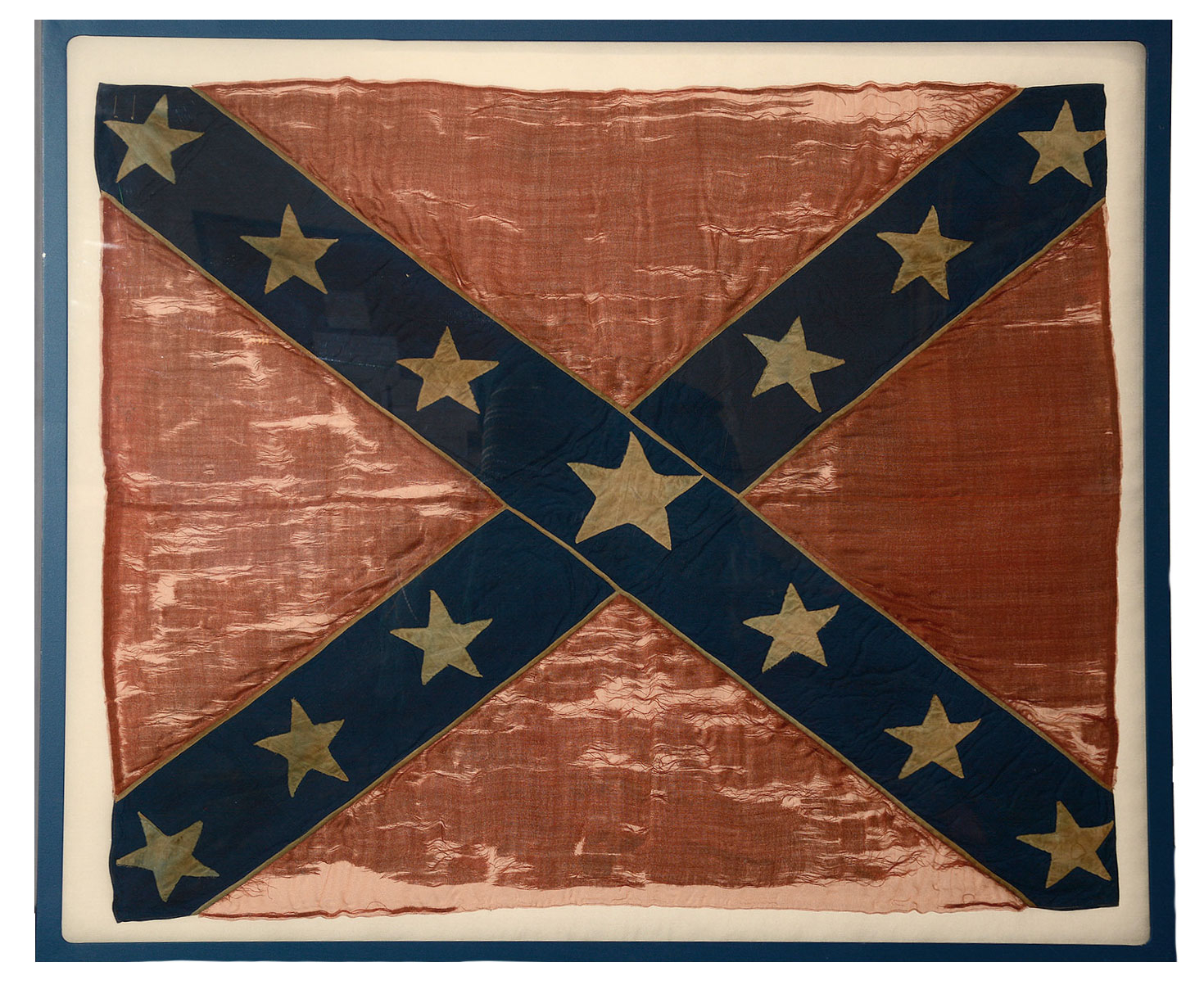

MORTON’S BATTERY FLAG OF FORREST’S CAVALRY: EX-GUNTHER COLLECTION, CHICAGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY, & TEXAS CIVIL WAR MUSEUM

Hover to zoom

$145,000.00

Quantity Available: 1

Item Code: 1286-621

Shipping: Determined by Method & Location of buyer

To Order:

Call 717-334-0347,

Fax 717-334-5016, or E-mail

This is one of two wartime Confederate flags flown by Capt. John W. Morton consecutively as guidons for his battery or simultaneously with one likely as the battery flag and the other as a personal or designating flag while Morton served also as Acting Chief of Artillery for Nathan Bedford Forrest. This flag was removed from its staff at the unit’s surrender in May 1865 by Hervy D. Burchett of Morton’s battery, who donated it to Charles Gunther for exhibition in his “Libby Prison War Museum” in Chicago in the 1890s, with the flag making its way into the Chicago Historical Society in the 1920s and into the Texas Civil War Museum in 1990. It has been published in Civil War Flags of Tennessee (2020) as Plate 135 with the editors of that volume noting, “Over the past 150 years, there has been much confusion and erroneous information associated with the history of this flag” (p. 476 and p. 474.) Unfortunately, they have rather added to the confusion and erroneous information, having failed to find Burchett’s full service record, which supports the history of the flag, and also misrepresenting an important 1977 letter from renowned vexillologist Howard Madaus, which establishes its provenance.

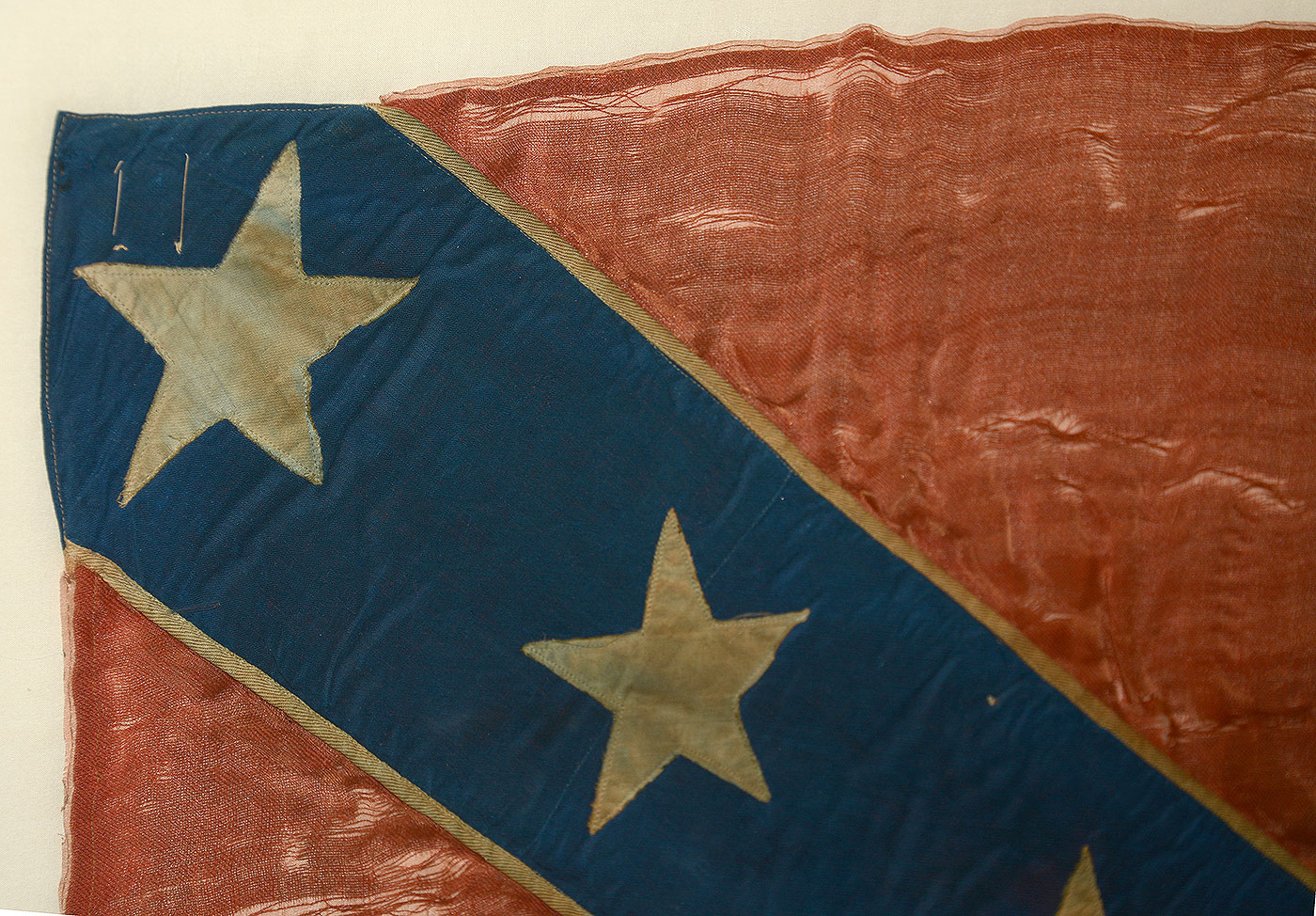

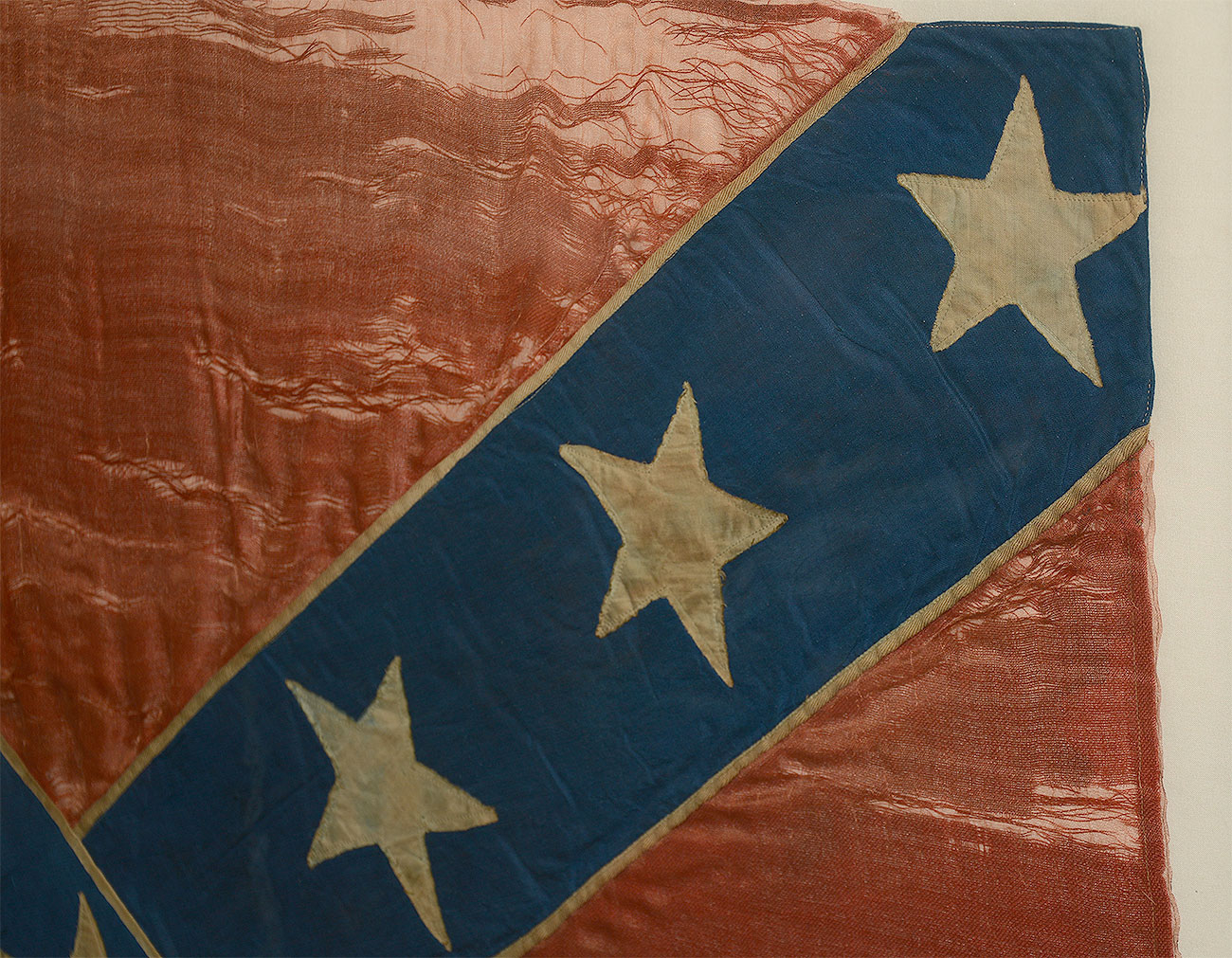

The flag measures 38” on the leading edge and 42” on the fly. It was archivally conserved, mounted, and framed, by the well-respected Textile Preservation Associates in preparation for its display at the Texas Civil War Museum and is largely intact, stable, showing field use and wear, but good color and retaining strong eye-appeal. Please see our photographs.

The TPA reports include the following overall description: “The flag is a Confederate Battle Flag with red quadrants, a blue St. Andrews Cross, thirteen white stars on each side, and a white twill weave fimbration binding the edge of the cross on both sides. . . There is no trim around the perimeter of the flag. The method of attachment is not apparent but there are small holes in the corners along the leading edge of the blue fabric, approximately 9" apart. The damaged blue fabric and dark stains suggesting prior attachment with tacks. . .

The fly is constructed of red wool bunting while the rest of the decoration is of cotton fabric, machine sewn throughout. The red fly extends underneath the cross and is constructed of two widths of fabric with a horizontal center seam. There is a selvage edge at the top and bottom edges of the top and bottom quadrants, while the leading edge and fly end are hemmed.

The arm of the cross that extends from the upper leading edge corner to lower fly corner crosses over the other arm on the obverse side. On the reverse side, the other arm of the cross is on top. The cross is made up of two layers of fabric, one appliqued to each side. 1/2" wide, white fimbration is wrapped around the edge of the long side of each arm of the cross like a seam binding outlining the long side edge of each arm. The star in the center of the cross is 5 1/2" across and the three stars on each arm of the cross are 4" across. . .”

The TPA analysis report includes examination of the fabrics, threads, dyes, stitching, etc. The conclusion notes, “the materials used in the flag are appropriate for the Civil War period. . . The flag appears to be made at one setting. . . The same sewing machine and thread appear to have been used throughout. . . The condition of all materials used in the construction of this flag have uniform wear and deterioration patterns. . .” The only anomaly noted was evidence the blue cross had carried twelve other, differently positioned stars for a time, as indicated by stitching holes visible between the stars on it. They do not venture an opinion on the reason, but the flag may have seen service for a time as twelve-star pattern, with the stars rearranged to make room for the larger central star during its period of use. Copies of the analysis, condition, conservation treatment reports, and instructions for handling and display by Textile Preservation Associates can be supplied to interested parties.

Along with the rest of the Gunther collection in the 1920s the flag passed to the custody of the Chicago Historical Society in the 1920s, who mistakenly cataloged it in the late 1920s or early 1930s as belonging to a Kentucky cavalry unit, having transposed two of Gunther’s labels, and the flag was deaccessioned with that incorrect identification in the mid-1970s. Howard Madaus detected and corrected the error in a 1977 letter to the then owner, a copy of which is included in the file. In addition to his analysis of the flag itself, Madaus notes Gunther’s labels had often been on paper simply pinned to the flags, something supported by the 1990 TPA report, which notes a shaded rectangular area on the flag where a label may have shielded the fabric from light damage. The error of attribution seems to have arisen from the CHS cataloger mistakenly applying the description of Flag No. 3 in Case No.17-3c to this flag, also Flag No.3, but in case No. 5-2C. (These descriptions appear on pages 35 and 33, respectively, of the catalog for “America’s War Museum,” part of the 1899 “Greater America Exposition” in Omaha, where the Gunther collection or at least parts of it were exhibited after Gunther shut down the Libby Prison Museum operation.)

The original description of the flag was thus actually:

“No. 3 - Confederate battery guidon made by a sister of Captain Marshall of Ga., who commanded the "Brown Horse Battery." This flag was presented to the battery at Dalton, Ga., in 1861, while attached to General Scott's command. After the Battle of Chickamauga, the battery was transferred to Gen. Forest's command and was then known as 2nd Tenn. battery (4 10-lb. rifled Dahlgren guns), commanded by Capt. Morton. The battery participated in the following battles and skirmishes, viz: Chickamauga, Nashville, Memphis, Tunnel Hill, Ga.; Harnettsburg, Brice's Cross R'ds., Miss., and Perryville, Ky. At the time of the surrender of Gainesville, Ga., H.D. Burchett, member of the battery, took the flag from the staff and concealed it in his saddle pocket. It has remained in his possession ever since.”

This description, relayed to Gunther by Burchett thirty years after the fact contains some errors, typographical or slips of memory, but Burchett (1842-1926) is well documented in the Confederate Compiled Military Service Records in the National Archives as a member of both Marshall’s and Morton’s batteries, providing a link between the two units of which the editors of CWFT were unaware, and who then cast doubt on Burchett’s history of the flag by stating, there is, “no evidence found to date showing any association” between Morton’s and Marshall’s units. Further, they misinterpret the date of Burchett’s earlier enrollment in a Tennessee cavalry company, March 16, 1862, as referring to his service in Morton’s battery, leading them both to assert that Burchett was “a member of Morton’s Battery (not Marshall’s Battery,)” and at the same time state that Burchett’s unit assignment “for the first six to nine months of Confederate service is unknown,” since they could not reconcile the March 1862 date to the history of Morton’s battery, which was only organized after he joined Forrest.

All of this led the editors of CWFT to suggest (p.474) that the references to Marshall’s company were somehow grafted onto the flag’s history with Morton. Worse, on p.476, they misrepresent Madaus’s letter on the flag, directing his remark, “While I am quite certain of the authenticity of the flag itself I’m not convinced that the history ascribed to it is the correct one . . .” against the Morton battery attribution, which is in fact Madaus’s own correction of the flag’s history and where his letter clearly shows he is referring to the mistaken Kentucky attribution. Similarly, on the same page they wrongly imply that his statement, “The design of the flag, i.e. battle flag, does not fit well with the history assigned to it. . .” refers to the Morton identification, whereas Madaus is again referring to the Kentucky misidentification. For his full rationale we refer interested parties to his letter.

Burchett’s service record, in fact, supports the history of the flag as he gave it to Gunther. Hervy D. Burchett (1842-1926) is well documented as being born in Virginia, with the family moving to Tennessee between 1842 and 1844, and with Burchett being found in the 1860 census living with his parents and eight brothers and sisters, helping to work the family farm in the Panther Creek District of Hancock County, TN. He enlisted March 16, 1862, in “Capt. William B. Jones Company Tennessee Cavalry,” which underwent several successive redesignations, ending up as Co. G, 5th (McKenzie’s) Tennessee Cavalry. CMSR files record his transfer from that unit to Marshall’s battery of artillery on June 16, 1863, both units then serving in J.S. Scott’s brigade of cavalry.

That is not to say Burchett’s account is error-free. His 1861 date for presentation of the Morton flag is clearly mistaken, but whether from a slip of memory or a typographical error is unclear. (Further, since Burchett joined Marshall’s unit more than six months after it was formed, his knowledge of the flag’s earlier history was secondhand.) Madaus thought 1863 was more likely for the flag’s presentation to Marshall’s company, though we might suggest late 1862. The company had been formed under Gen. Kirby Smith’s direction in September 1862 and was not completed until November, after being redesignated horse artillery, at which point by Marshall’s own account, he journeyed to Augusta, Ga., to obtain “harness, traveling forge, and cavalry equipment. . .” Presentation of a flag in Georgia at about point in time is thus possible, and we also note that a South Carolinian, Marshall had acted as Artillery Instructor for the 12th Georgia Battalion of Artillery as a lieutenant in 1862, perhaps helping to explain Burchett’s recollection of Marshall’s background and the flag’s ultimate origin. When the alteration of the star arrangement took place remains unclear, but similarities of the flag to that of Freeman’s Tennessee Battery are noted by CWFT, where it is pictured as Plate 134 and dated “probably 1862 or 1863” (p.471.) For notes on the battery, see Tennesseans in the Civil War, 1964.

Burchett’s list of engagements is more problematic and may represent a combination of his own experience with battles and more general campaigns during its period of use. Harnettsburgh is puzzling but may be a slip for Harrisburg, i.e. Tupelo, fought in July 1864. Perryville may reflect of his own earlier service in the Tennessee Cavalry. Brice’s Crossroads, however, is precise and was likely memorable: Burnett is recorded in the CMSR files for Morton’s battery as having been “wounded slightly” in the battle in June 1864, and he certainly appears on the roll of prisoners of war of Morton’s Battery, surrendered by Taylor to Canby at Citronelle, AL, and paroled at Gainesville, in May 1865.

Burchett’s statement that Marshall’s battery essentially became Morton’s is, of course, wrong, but his statement that the change took place “after the Battle of Chickamauga,” i.e. September 1863, likely reflects the disbanding of Marshall’s battery about that time and his own transfer to Morton’s battery. “Tennesseans in the Civil War” gives the last official mention of Marshall’s battery as August 7, 1863, when it was at Stanford, TN, following its participation the raid of Col. J.S. Scott’s brigade into Kentucky, with fighting at Rogersville and Stanford. Marshall himself had left the battery considerably before that, as early as March, and took a staff post, with command of the battery passing to a “Capt. J.W. Stokes.” The flag, however, being a battery flag would have remained with the unit. Printed notes on Burchett’s CMSR card for the unit note only that the company, had been, “composed partly of men detailed from other organizations and it was evidently disbanded for some of the men are found to have subsequently served in other commands.”

A September-October 1863 date also fits Burchett’s documented service with Morton. A date of transfer is not stated, but he first appears on the CMSR file card made from Morton’s September-October 1863 muster roll. Burchett does not say explicitly he was the one who brought the flag into Morton’s battery. He may well have, though he may not have been the only one of Marshall’s men to join Morton, at least for a time. Morton says on p.120 of his “Artillery of Forrest’s Cavalry” that he received two guns captured by Cleburne’s division at Chickamauga, increasing his battery to six guns, which likely called for extra manpower at least for a time. By late October and early November, however, with Morton’s transfer with Forrest to Okolona, MS, after Forrest’s fall out with Wheeler and Bragg, the battery was back to four guns, as mentioned by Burchett, and just 67 men, though with Burchett among them: one of the few other CMSR cards in his file is the transcription of his listing as “present” on Morton’s November-December 1863 muster roll, by which time Forrest and Morton were in Mississippi with their reduced force and were endeavoring to build up their corps again, where the flag may have been a useful recruiting tool as well as a guidon and rallying point in battle.

Editors of CWFT also discuss the other flag associated with Morton: a smaller, guidon-size color, 16-3/4” by 25-3/4” including fringe, carrying the initials “M B” in large letters stitched to it (i.e. “Morton’s Battery” if not “Morton’s Battalion.”) That flag is illustrated and discussed in CWFT as Plate 136, and pages 477-478. It surfaced at a Morton family estate sale in 1983. It is difficult, however, to separate family lore and its romantic, if not romanticized, history from more solid information. Family tradition was that it was sewn by Morton’s future wife and presented to him, though the exact date and nature of supporting documentation is unclear. Even the editors of CWFT fluctuate between dating the flag to sometime after the couple’s initial meeting in Spring 1863, and dating the flag itself to Spring 1863. (We note they did not actually marry until 1868, so the courtship may not have proceeded at lightspeed.) In any case, the flag is accepted as a wartime creation and there is no reason to doubt a Morton connection.

Unfortunately, the editors of CWFT use what was clearly a personal flag to question the flag brought back by Burchett from the battery’s surrender in 1865, asking rhetorically, “Could Captain Morton have flown two flags during the last two years of the war? This is not likely, but not impossible. Could the flag, brought home from Alabama by H. D. Burchett, have been one issued to Morton's Battery after he joined General Forrest's forces in December 1862 and used until his future wife made one for him in the spring of 1863? This is possible. But no records have currently been found documenting the presence and use of this flag prior to its being brought home by H. D. Burchett.”

Needless to say, it is all in the phrasing, and the question was fueled by lack of information about Burchett’s record, which clearly indicates that he and likely the flag arrived in Morton’s battery in Fall 1863, and rather begs the question in stating the Morton family flag was made for Morton in Spring 1863. Whichever flag arrived first, however, neither flag invalidates the other and the answer to their question is an emphatic “yes:” Morton could well “have flown two flags” in the last two years of the war, or at least from May 1864 forward, when he was appointed by Forrest as Acting Chief of Artillery, giving him a battalion to command, a staff to manage, and handed day-to-day operation of the battery to Lt. Sale.

This is a world-class Confederate flag from one of the most, or perhaps the most dynamic Confederate units. Morton became one of Forrest’s most trusted officers, moving up from a temporary command of two guns in September 1862, to command of a battery of four in December, and then appointment to command of Forrest’s entire artillery battalion in May 1864. Morton played a key role in that general’s aggressive strategy and tactics that relied upon taking the offensive whenever possible and produced trouble for his opponents far beyond the actual numbers of his command. After serving under Morton and Forrest, Hervey D. Burchett returned to Virginia after the war, filing for a pension there in 1900. Both his pension application and his headstone proudly note his service with Morton’s battery, which took place under this flag. [sr] [PH:L]

EXTRA SHIPPING REQUIRED.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

CLICK HERE FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About MORTON’S BATTERY FLAG OF FORREST’S CAVALRY: EX-GUNTHER COLLECTION, CHICAGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY, & TEXAS CIVIL WAR MUSEUM

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Selection Of Unframed Prints By Don Troiani »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

featured item

RARE “SNELL” SWORD BAYONET – M1841 RIFLE, CIRCA 1855

Scarce “Snell” or “ring-style” sword bayonet for the Mississippi Rifle. When it became evident that riflemen needed a bayonet to put them on equal footing with regular musket-armed infantry in close combat, several methods of attaching long… (490-7260). Learn More »