site search

online catalog

THIRTEEN STAR U.S. NAVY BOAT FLAG FOR THE GUNBOAT U.S.S. METACOMET

Hover to zoom

$20,000.00

Quantity Available: 1

Item Code: 1284-13

Shipping: Determined by Method & Location of buyer

To Order:

Call 717-334-0347,

Fax 717-334-5016, or E-mail

(The following is from a yet larger document of authenticity and history by this country's flag expert and historian Mr. Gregory Biggs, Clarksville, Tennessee). "Thirteen-star boat flags from the U.S. Navy of the Civil War era are uncommon flag outside of museums. There is a bit of a misconception about boat flags and not that much has been written on these by modern flag scholars that correctly states what these were used for. The larger ships’ ensigns and storm flags tend to get a lot more attention than boat flags and yet the latter were also used as ensigns on certain classes of smaller warships.

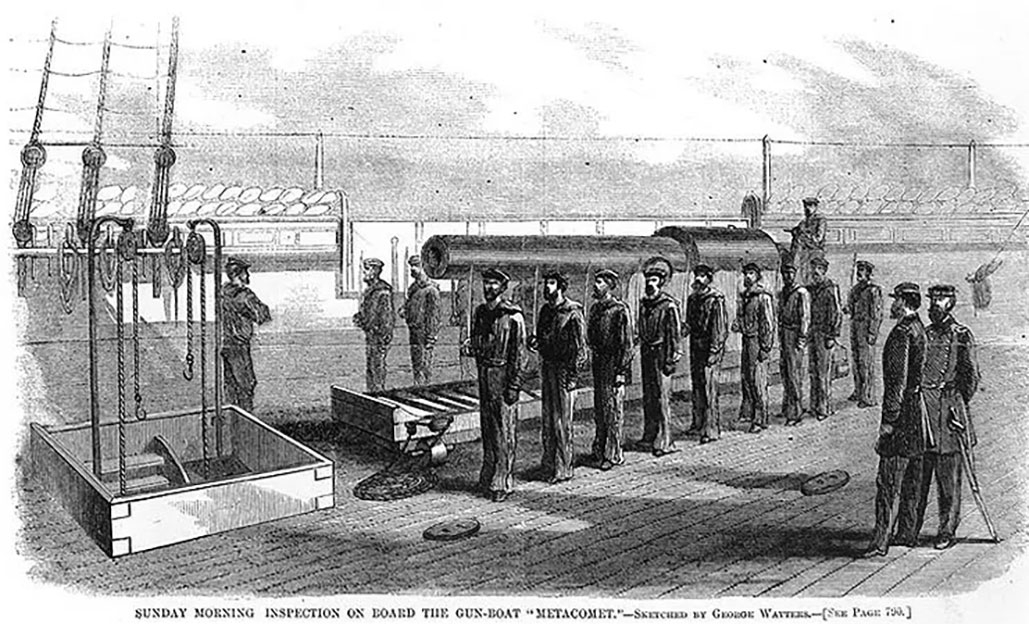

USS METACOMET. Unlike many of the early warships added to the rapidly expanding U.S. Navy after the war began, many of which were often conversions from civilian craft or smaller gunboats, the Sassacus Class were all purposely built as warships. Every ship of the class was laid down starting in September 1862, continuing into November. These ships began launching in December 1862 continuing into October 1863 with most of them hitting the water between March and May. Commissioning into service began in October 1863 with most from February 1864 until August. Two of the class were not commissioned until 1865 and one ship was never given her commission. A total of twenty-eight ships of this class were built. The U.S.S. Metacomet was part of this class. She was laid down at the Stack Shipyard in South Brooklyn in 1862 and was launched on March 7, 1863. Weighing 1173 tons, she was 240 feet long, 35 feet wide and 9 ½ feet high. Propelled by a sidewheel on each side of her wooden hull she could make 13 knots and with her two masts could also use sail power when needed. Two hundred men made up the crew. By March 1864, Metacomet carried a formidable battery of two rifled 100-pound guns, four 9 Inch smoothbore guns, two 24 pounder guns and two rifled 12 pounders.

She was commissioned on January 4, 1864, and was captained by Lt. Cdr. James Jouett. Assigned to the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron, the Metacomet chased the blockade runner Ivanhoe forcing her to the shore on June 30th. Her next engagement was the Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5th as part of the fleet that ran Fort Morgan and Fort Gaines under the command of Admiral David Farragut. She would later take part in the bombardment of Fort Morgan from August 9-23rd, 1864. After the war, U.S.S. Metacomet was decommissioned on August 18th, 1865, and was sold on October 28, 1868.

USS METACOMET VERSUS THE C.S.S. SELMA MOBILE BAY. Mobile, Alabama was a major blockade running port on the Gulf of Mexico. Along with Galveston, Texas and Matamoros, Mexico, Mobile would see a lot of tonnage brought in via Havana, Cuba which was the trans-shipment port for the blockade runners for the run to the Gulf ports. There were other smaller ports for the blockade runners, usually smaller ships like sailing schooners, along the gulf coast, in particular St. Marks in Florida, but of them all, Mobile was the king. Supplies run into this port were used by the Mobile Quartermaster and Ordnance Depots for distribution primarily to the Confederate Army units of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana. Other items were shipped to Atlanta and other points in the Deep South.

The main entrance to Mobile Bay was defended by Forts Morgan (46 guns) on the right side of the channel (Mobile Point, a peninsula attached to the land on the east side of the bay) and Fort Gaines (26 guns) on the left side (Dauphin Island), part of the masonry forts built after the War of 1812 to protect the long American coast, along with Fort Powell (18 guns), a sand fort backed with wood on an artificial island north of Fort Gaines that protected the west side entrance into the bay at Grant’s Pass.

Additional defenses included obstructions in the center of the main channel plus a field of torpedoes (mines) that were to the right which were anchored closer to the Fort Morgan side of the channel. These would force Union warships closer to the fort’s guns. These were marked so that friendly ships could safely enter the bay. Fort Gaines had shoals on its front that forced ships to the eastern side as well and these were tied into the emplaced obstructions. Backing up the forts and torpedoes was a small Confederate Navy squadron. The CS Navy flotilla was anchored on the ironclad CSS Tennessee (6 guns protected by 5 to 6 inches of iron plate), built at Selma Naval Works and modified at Mobile. The flotilla, under the command of Admiral Franklin Buchanan, also included the wooden gunboats CSS Selma (four guns although another source says eight), CSS Gaines (6 guns and partially covered with 2 inches of iron) and CSS Morgan (10 guns, later reduced to 6 and partially armored).

Facing the Confederates was a large fleet under Admiral David Farragut featuring a mix of ocean-going steamers and several turreted ironclads. This fleet consisted of the USS Hartford, Farragut’s flag ship (screw sloop, 23 guns), USS Brooklyn (screw sloop, 21 guns), USS Lackawanna (screw sloop, 12 guns), USS Ossipee (screw sloop, 13 guns), USS Richmond (screw sloop, 22 guns), USS Seminole (screw sloop, 9 guns), USS Oneida (screw sloop, 10 guns), USS Monongahela (screw sloop, 7 guns), USS Galena (ironclad screw steamer, 6 guns) USS Metacomet (steam gunboat, 10 guns – another source states 9 guns), USS Octorara (steam gunboat, 6 guns), USS Port Royal (steam gunboat, 17 guns), and the gunboats USS Itasca (5 guns) and USS Kennebec (5 guns). Supporting this fleet were four turreted ironclads: USS Chickasaw (two turrets, 2 guns), USS Manhattan (single turret, 2 guns), USS Tecumseh (single turret, 2 guns) and USS Winnebago (two turrets, 2 guns).

Farragut’s plan included a force of 1500 Union troops under General Gordon Granger who would be landed on Dauphin Island and lay siege to Fort Gaines focusing their efforts to deal with that threat. This part of the campaign began with their landing on August 3, 1864.

On August 5th, by 5:30 AM, Farragut formed his fleet into a column. Next to his larger sloops, he had lashed to their port sides away from the guns of Fort Morgan, a second series of ships. To their right came the ironclads. Aware of the torpedoes in his left front, Farragut made the call to run the channel into the bay with his famous battle cry, “Damn the torpedoes, full steam ahead.” His risky move would cost him the lead ironclad USS Tecumseh which struck a torpedo and sank within minutes. The map below shows Farragut’s ship alignment.

As the map shows, the USS Metacomet was lashed to the USS Hartford which was the second ship in the column. This was done to keep the side-wheelers from fouling on the obstructions. Once his ships were past Fort Morgan, the ships lashed to the right-side ships were cut loose to spin into the bay and help engage the Confederate flotilla. Led by the USS Brooklyn, Farragut had ordered his larger ships to use grapeshot from his upper deck guns to fire on the upper battery of the fort to pin down the men manning those guns. In this manner he was able to pass the fort with minimal damage and then prepare to engage the Confederate Navy. Despite that the rebel fire was treacherous.

Louis Prang’s famous painting of Farragut’s fleet passing Fort Morgan showing the Tecumseh sinking and the larger ships with their consorts lashed to them as the CSS Tennessee, CSS Morgan and CSS Gaines move in to engage.

Being the largest and most powerful Confederate warship, the CSS Tennessee drew a lot of attention. As Farragut’s fleet passed into the bay some of his ships engaged the CSS Gaines and CSS Morgan. The Gaines was soon disabled and beached on Mobile Point east of Fort Morgan. The CSS Morgan basically withdrew from the fight heading east. She would be the only Confederate ship to survive the fight and would serve the Confederate Navy until the end of the war.

The CSS Tennessee sailed up the line of ships into the bay raking them as she passed. With more room to maneuver, Farragut’s commanders moved their ships to fire back and even ram the rebel ironclad which several would do. Surrounded by several Union warships, her gunport doors jammed shut and Buchanan wounded by a sharpshooter from the mast of one of Farragut’s vessels, the Tennessee struck her colors.

The map below shows Farragut’s movement into the bay and the fighting between the fleets.

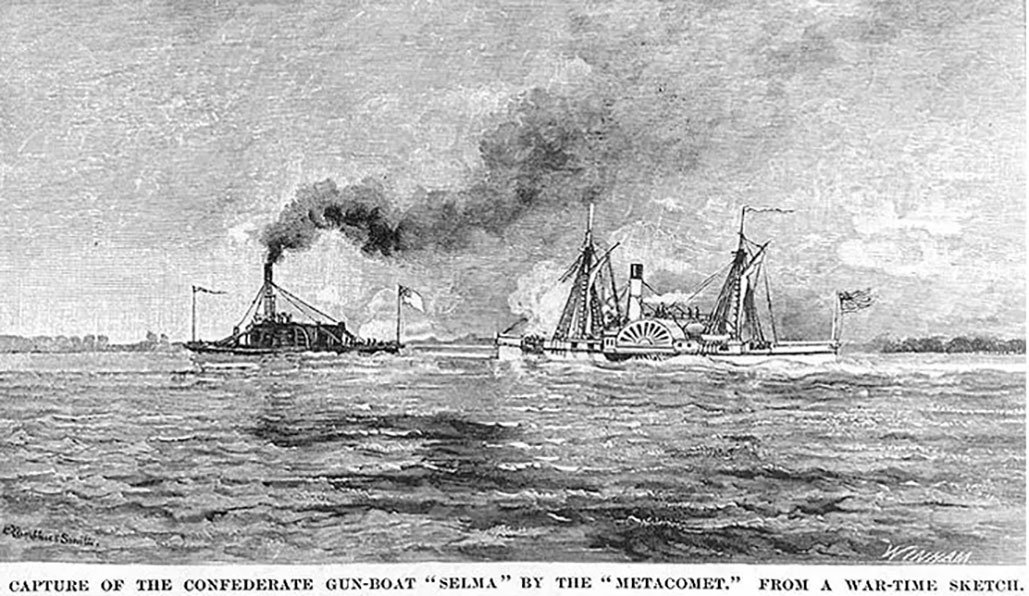

With the CSS Gaines disabled and captured, and the CSS Tennessee having surrendered, the final combat between ships was the USS Metacomet versus the CSS Selma, the least powerful of the Confederate fleet.

The CSS Selma began life as the packet steamer. Built in Mobile in 1856, she sailed the coastal trade between ports along the Gulf coast. With the coming of the war, she was converted into a warship starting in April 1861 with her hull being strengthened to be able to handle the weight of her four-gun battery which was pivot mounted on the centerline. (NOTE: historian Robert Browning states that in the battle the Selma carried four 32-pounders which were smoothbores, one 8 inch Brooke rifle in the bow and one 6.4 inch Brooke rifle on her stern – the four extra guns probably added much later.) Light armor had also been added for further protection. Initially named the CSS Florida, by November she was in action as part of the New Orleans defense flotilla.

Her service was mostly in Mobile Bay, but she also ventured into Mississippi Sound escorting blockade runners as they left the bay but also engaging U.S. Navy warships including the USS Massachusetts in October 1861 which she badly damaged with a shell from her 6.4 Inch rifled pivot gun. In December she took on the USS Montgomery who did not have the firepower to deal with Florida’s rifled gun. These forays certainly gained the respect and notice of the U.S. Navy ships deployed to the Gulf region not only for her firepower but also the threat to the Union base on Ship Island from which would come the campaign to take New Orleans in April 1862.

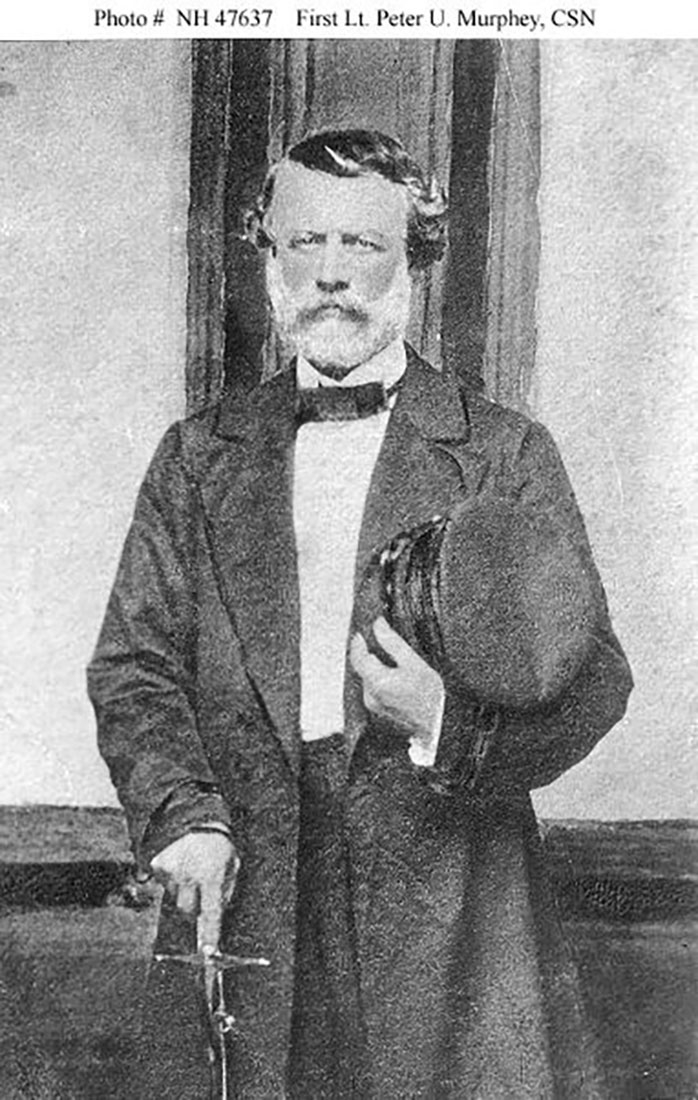

In July 1862, the ship was renamed as the CSS Selma. This was due to the raider CSS Florida being commissioned into service to raid Union commerce. Lt. Peter Murphey, a former US Navy officer, was named to command which he would retain through the Battle of Mobile Bay. In February 1863 she was sent with 100 men aboard to capture a Union blockade ship and while sailing the bay at Dog River Bar she ran hit a snag and sank. Thankfully she foundered in only eight feet of water and was raised and back in service a little over a week later.

As Farragut’s fleet ran into the bay, the Selma began firing on the USS Hartford. The steady fire on the flagship caused Farragut to cast off the USS Metacomet to drive the Selma away. In a running fight with the Union vessel, the Selma, seeking to reach shallow water, was overtaken by the Metacomet, a faster and more heavily armed ship, and she struck her colors and surrendered. The chase had gone over eight miles into the bay and took about an hour.

It had been Murphey’s hope to lure the Metacomet into shallow water where she would run aground due to her drawing nine feet of water versus Selma’s six feet. Indeed, at one point, a sailor on the Metacomet noted that she only had a foot of water beneath her keel. The Selma’s casualties included Lt. Murphey who along seven others, was wounded while eight men were killed. The Selma’s flags were taken as prizes.

Taken into Union service, the USS Selma served Farragut’s fleet in Mobile Bay through the end of the war, including helping to bombard Fort Morgan. After the war she was sold to civilian service and sank on June 24, 1868 off Galveston, Texas.

Historian Jack Friend in his book on the battle, noted the pre-war friendship between Lt. Patrick Murphey of the Selma and Lt. Cdr. James Jouett of the Metacomet based on their service together in the old navy. Knowing that Murphey commanded the Selma, Jouett made ready the “good wines and cigars” that he retained for when they were together again. Additionally, Jouett, “directed this steward to purchase some crabs and oysters and out them on ice.” Historian Robert Browning noted that Jouett stated to Murphey after coming on board Metacomet trying to sooth his friend’s feelings after surrendering, “Pat, don’t make a damned fool of yourself, I have had a bottle on ice for you for the last half hour!” Murphey replied, “Why didn’t you let me know you had all this? I would have surrendered sooner!” After the surrender a sumptuous lunch was enjoyed by both men and Jouett returned his friend’s sword that had been taken initially.

Indeed, Jouett’s friendship with Murphey dictated how he dealt with Selma during the pursuit. As he reported, “I was only about two hundred yards from her (the Selma); as she was running into shoal water, where the Metacomet could not go, I concentrated the entire battery upon her; giving the strictest orders not to fire a gun without my command to fire. I directed the bow gun, a 100-pounder; to be fired; this was enough. Had I fired the broadside, I knew but few would have survived, she was so close and at our mercy. I was not killing my countrymen recklessly. I fired the one gun, and that was enough; it killed an officer; wounded the captain and five men, I think. My men were mad to fire, but I held their fire. I knew that as soon as the men on the Selma could get to the flag, they would have it down, and they did.” A full broadside would have devasted the Selma.

After the battle’s conclusion, the Metacomet assisted in the recovery of sailors from the sunken ironclad USS Tecumseh, an action for which several crew members were awarded the Medal of Honor.

In mid-August, Farragut sailed some of his smaller warships closer to Mobile to take on the two stationary rebel ironclads there, CSS Huntsville and CSS Tuscaloosa. His flag ship for this expedition was the USS Metacomet.

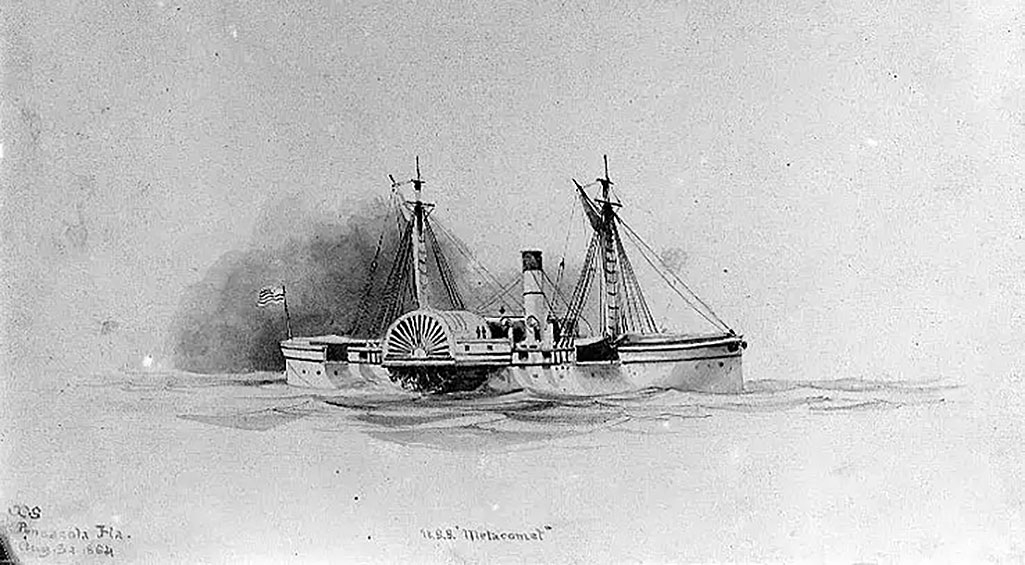

Illustration Showing the USS Metacomet Flying Four Flags. While some think this might be a fanciful artistic interpretation, there were instances of Union warships going into battle with more than just their commission pennant and ship’s ensign flying from the stern mast. When the USS Kearsarge fought the CSS Alabama off Cherbourg, France, Captain John Winslow ordered flags flown from every mast of his ship, which totaled three plus the stern ensign which would have been the largest. As ships carried spare flags, this would have been possible using storm flags and some of her boat flags. Note the two smaller US flags flying from the Metacomet’s masts. Interesting to this image is that the Metacomet’s jack is shown flying from the bow staff while in the battle. Typically, jacks are only flown while the warship is in port.

Historian Jack Friend states in his book on the battle, “As the Union battle line advanced with flags flying from every peak…” which he further states took place as the column of Union ships closed on Fort Morgan and the waiting Confederate flotilla. In his footnote he cites the memoir of U.S. Navy captain Henry Walke. Walke was an ironclad skipper on the Mississippi, Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers during the war. He was not at Mobile Bay but his memoir states this came from a letter written to someone in New York from one of the crew of the flagship Hartford. The letter stated, “all being ready, the signal was made for the fleet to advance. Our ships advancing, with a beautiful flag at each masthead, presented a scene worthy of the brush of an Angelo or Raphael.”

Historian Robert Browning corroborates the flags story in his book stating, “As the ships got into their positions in the battle line, they all hoisted an American flag at each masthead. One of the men remembered that the flags made it appear as if they were preparing for a ‘gala day’.” Another of the Hartford’s crew wrote that he, “could see the mass of colors grandly unfurled by the strong westerly breeze.”

A perusal of the Navy Official Records on this battle made no mention of the fleet doing this from Farragut’s several reports or that of Captain Percival Drayton, skipper of the USS Hartford.

U.S. NAVY BOAT FLAGS. The USS Metacomet flag is an excellent example of a thirteen-star boat flag. Prior to the Civil War, the U.S. Navy would create categories of flags etc. based on the rating of the warship involved. This rating included the overall size of the warship by weight, size of the crew, how many guns she carried, etc. Thus, the larger the ship the bigger the flags had to be with Ships of the Line carrying the biggest battle ensigns, storm flags, etc. while lesser ships such as brigs, frigates, sloops down to tugs would need smaller flags. By 1863, even though similar designations and rankings existed in the Navy in the 1850s, this charted out to four ship rating classifications with fourteen specific flag sizes. Each rating stated the sizes of each type of flags to be carried by that warship along with how many. Flag Sizes Ten through Fourteen were considered Boat Flags meaning that although these smaller flags would be flown from a ship’s launches and her Captain’s Gig, they were also used by the smallest of the warships in the fleet from river gunboats, smaller blockading ships, supply ships to tugs.

Storm flags would be the smaller versions of the battle ensign, again determined by the rating of the warship involved. Warships also carried jacks, to be flown from the bow staff only when the ship was in port, a set of signal flags and, for the ocean-going vessels, a series of foreign flags for saluting purposes and this would be based on what station the ship was posted to.

The U.S. Navy Table of Allowances specified how many of each type of flag was to be carried by a warship based on its rating. Spares were carried to replace flags damaged by normal use or battle. Sailors also made any needed repairs to flags while at sea and spare bunting was carried for this purpose. The home port navy yard was the primary supplier for flags and other supplies for warships based at that port. Often, flags were marked on the hoist edge by the yard that made them. The Western Blockading Squadron used Ship Island in the Gulf as its base but repairs etc. had to be made elsewhere, certainly in Pensacola, Florida, the former U.S. Navy yard taken by the Confederates in 1861 and had been retaken by the Federals in May 1862. This is most likely where flags for the warships of this squadron were made although it could have been made at the New York Navy Yard which was the yard closest to where the Metacomet was built. The flag is of uniform construction identical to other Boat Flags I have seen.

As mentioned, the U.S. Navy considered flags from Rating Ten through Fourteen to be Boat Flags. These were of the Stars and Stripes pattern. Some of these would be for smaller warships as ensigns but any larger warship that carried launches also had a boat flag for each launch including the captain’s gig. The 1854 Regulations had what would be considered Rating 13 and 14 as flags measuring 3.75 by 7 feet and 3.25 and 6 feet respectively. By 1864, these had been changed to 3.20 feet by 6 feet and 2.50 feet by 5 feet. As with the larger flags, these too were made of imported wool bunting.

It is not exactly known when the Navy began to use boat flags but they began to appear between 1853 and 1857. Since smaller flags made it difficult to place the number of stars for states at the time, boat flags with sixteen stars showed up in the 1857-time frame. There has been some discussion between flag historians that the flags had something to do with the sixteen free states. The new Republican Party allegedly began to use (and were so accused by the Democrats) sixteen-star flags for the John C. Fremont campaign which riled the Democrats. These flags carried over into the 1860s Campaign and were dubbed “Exclusionary Flags.” Another theory is that the sixteen stars represent the number of states when the U.S. Navy was officially formed in 1798.

Sixteen-star boat flags were used between 1857 through 1861. An existing example is on from the famous U.S.S. Cumberland, sunk in action in 1862 in a battle with the C.S.S. Virginia. The stars in the cantons were placed in four rows of four stars from top to bottom.

In 1862, the flags were changed to thirteen stars, probably in honor of the original thirteen colonies. These appeared in the canton in two formats; 4-5-4 in three rows from the top and 3-2-3-2-3, which seems to be the more common based on surviving flags. This pattern would continue into the 20th Century ending in 1916. The modern Navy uses boat flags with fifty stars today.

THE OFFERED FLAG OF THE METACOMET. The flag, as it currently is, measures 42 inches on the hoist by 53 inches on the fly. This end is tattered and certainly missing a significant portion of the flag which was souvenired. The cuts on the fly end are uniform in that it is close to a straight line from top to bottom. Had this been due to wear the flag would have worn on the fly end unevenly. Based on the 1863 Regulations for Navy Flags, this corresponds closely to a No. 12 Boat Flag which was to measure 3.70 feet on the hoist by 7 feet on the fly. This means the fly end is missing about 31 inches. Two pieces of the bottom red stripe have also been removed as souvenirs. The piece closest to the hoist edge is 13 ½ inches long while the piece closest to the fly edge is 13 ¼ inches. The cuts here are identical to those on the fly end.

Three of the stars on the reverse side have some damage, two of which show some burn marks. The stars appear to have some level of smoke on them, probably from use as the flag of the CSS Selma after her capture if this theory is correct. A forensics study would confirm this thesis.

Further details follow:

Stars – Thirteen, white polished cotton, measuring 5 inches to 5 ¼ inches across.

Canton – 30 5/8 inches by 22 ¾ inches, wool bunting. The reverse side has a field repair measuring 4 ½ inches by 3 ¼ inches. This only shows on the obverse side thanks to the stitches used.

Stripes – Thirteen, measuring from 3 inches wide to 3 ½ inches. Most are 3 ¼ inches. Sewn together with flat fell seams, wool bunting

Lettering – “Metacomet” is stenciled on the hoist edge. The three larger letters (M and two T) are 1 ¼ inches tall. The other, shorter letters are ¾ inches tall. The name is 9 5/8 inches long.

Hoist Edge – Cotton canvas, 1 7/8 inches wide (folded over the hoist edge of the flag). The hoist edge has two whipped eyelets. Boat flags either have these or metal grommets. The whipped eyelets show slight wear from some level of use.

The Regulations for U.S. Navy ships offered four classifications of warships based on their type and weight. As the USS Metacomet weighed about 1173 tons that places her as a Second-Rate warship. For Paddle-Wheel steamers the breakdown was from 1000 tons to 2400 tons.

This 1863 flags chart shows the Numbers 10 through 14 being listed as Boat Flags. Number 12 is the existing boat flag of the USS Metacomet.

The 1864 Table of Allowances dictated what sorts of equipment, other than armament, that warships were to carry. A Second-Rate ship like the Metacomet was to carry the following flags based on the Numbers 4, 5 and 6:

Ships ensign – anywhere from two to four flags which would include its storm flag. These would measure 10 feet by 19 feet to 13.20 feet by 25 feet. Commissioning pennant – two to three measuring .30 feet by 20 feet to .40 feet by 30 feet.

Jacks – one to three measuring 5.40 feet by 7.60 feet to 7 feet by 10 feet.

Boat flags – the number would depend on how many launches a warship carried – one being the Captain’s Gig. Based on the photographs of the other ships of the same class as Metacomet there are four launches hanging from side davits. It is not known if she also carried a Captain’s gig set on the deck between the paddle wheelhouses. She definitely had at least four Boat Flags and if she had a gig, it would be five in all. One of these was probably used to fly over the captured CSS Selma.

Additional flags could be for Flag Officers, task force commodores along with sets of signal flags. Deep ocean-going warships also carried foreign flags for saluting purposes. Farragut’s flag would have been hoisted on the Metacomet when he used her as his flag ship to go after the immobile Confederate ironclads closer to Mobile.

While there might be other flags from the U.S. Navy warships involved at Mobile Bay in museums, I have not been able to locate any. The museum at the U.S. Navy Academy does not seem to hold any flags from Farragut’s fleet based on the museum’s book on trophy flags. A cursory search online in the collections of the American Museum of History of the Smithsonian Institution, shows no flags from Farragut’s fleet. There is his post-war four-star admiral’s flag which Farragut flew after being promoted to the Navy’s senior admiral and four stars. The USS Hartford has several flags available including a star from the 1861 flag of the USS Hartford and a portion of a flag including some of its canton and stars in a private collection from the USS Hartford from the war, but it is not known if this was at Mobile Bay. A picture from the 1940s or 1950s exists of several men holding a large flag of the ship but it is not known from what period of her long career it is from. Skinner Auctions in 2015 sold a blue signal flag from Hartford but no mention of it being at Mobile Bay can be found. The Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis holds a thirteen-star boat flag from the second cutter of the Hartford that could be from Mobile Bay but their accession records do not clarify this. The star pattern of 5-3-5 is atypical of the boat flags of their era which were mostly 3-2-3-2-3.

Thus, failing the turning up of another flag from a different source or distinct confirmation that one of the Hartford’s flags is from August 1864, the boat flag of the USS Metacomet is probably the only known surviving U.S. Navy flag from the Battle of Mobile Bay and the only surviving flag from her flag compliment. That makes it a very important relic for collectors.

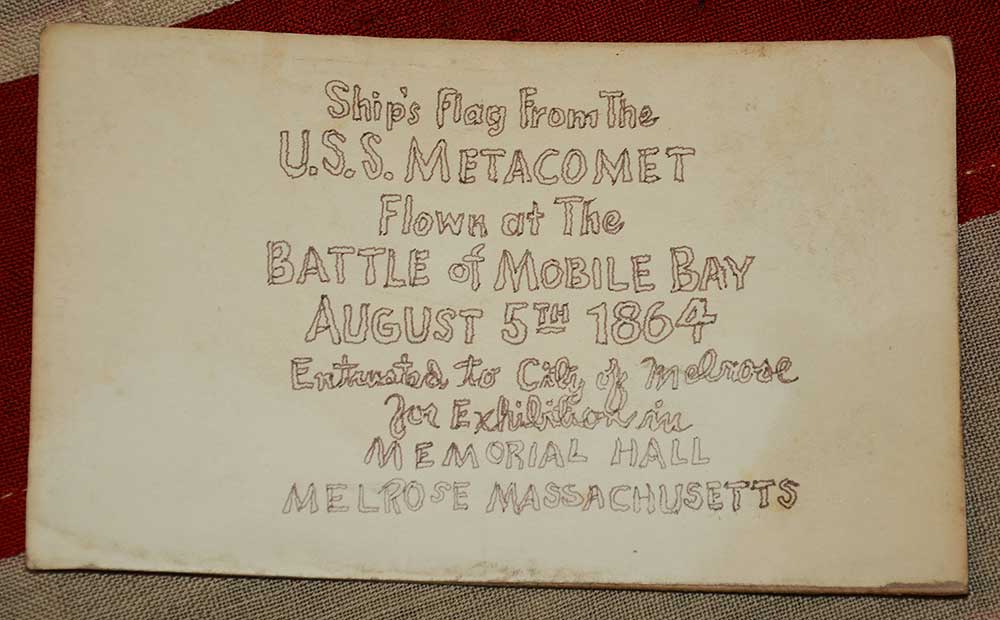

The Provenance of the USS Metacomet Boat Flag

After the Civil War, Union veterans formed the Grand Army of the Republic. Each state had chartered chapters where veterans would meet, hear lectures, fund raise for monuments and other affairs. Some of these became museums for Civil War relics, both Union and Confederate. Most have folded over the years and many of their relics dispersed across the country into private collections while other relics remain missing.

The Metacomet’s flag came from the U.S. Grant GAR Post 4. Chartered on February 19, 1867 in Melrose, Massachusetts, the post lasted until 1945. The flag was donated to the post by Mayo Dyer Hersey, a prominent engineer, scientist and Brown University professor. He had been involved with the Grant Post over his life and made the donation of several items including the Metacomet’s boat flag. Hersey was related to Captain Nehemiah Mayo Dyer, who was aboard the Metacomet at Mobile Bay as an Acting Master. According to Lt. Cdr. James Jouett’s Official Records report, “at 9:10 the Selma struck her flag to this ship. I immediately dispatched a boat, in charge of Acting Master N.M. Dyer, to take charge of the prize and to send her captain and first lieutenant on board. He hoisted the American flag and reported Captain Murphey wounded…” Jouett later stated, “For the efficient handling of the vessel I am much indebted to Acting Master N.M. Dyer, who had permission to go north on leave, but volunteered to remain to assist in the attack upon the forts.”

It is apparent that Jouett depended on Dyer to be an important cog in his crew and appreciated him staying with his ship for the battle. What was the flag that Dyer took with him to hoist over the Selma? It is highly doubtful that the Metacomet lowered her main ensign to use for this capture especially was it was a smaller ship and once taken into US service, Selma would have been issued a new compliment of flags. Instead, Jouett probably gave Dyer one of the boat flags of his ship to use. Smaller than the ship’s ensign and storm flag, all the Selma needed on its flag staff was some American flag to show it had been captured. Was it this flag? Quite possibly. The key thing to keep in mind is why would Dyer be able to retain one of the Metacomet’s flags if it wasn’t the one he took to fly over the Selma and why was it souvenired as much as it was? This makes complete sense as does why it was donated to the GAR hall later on.

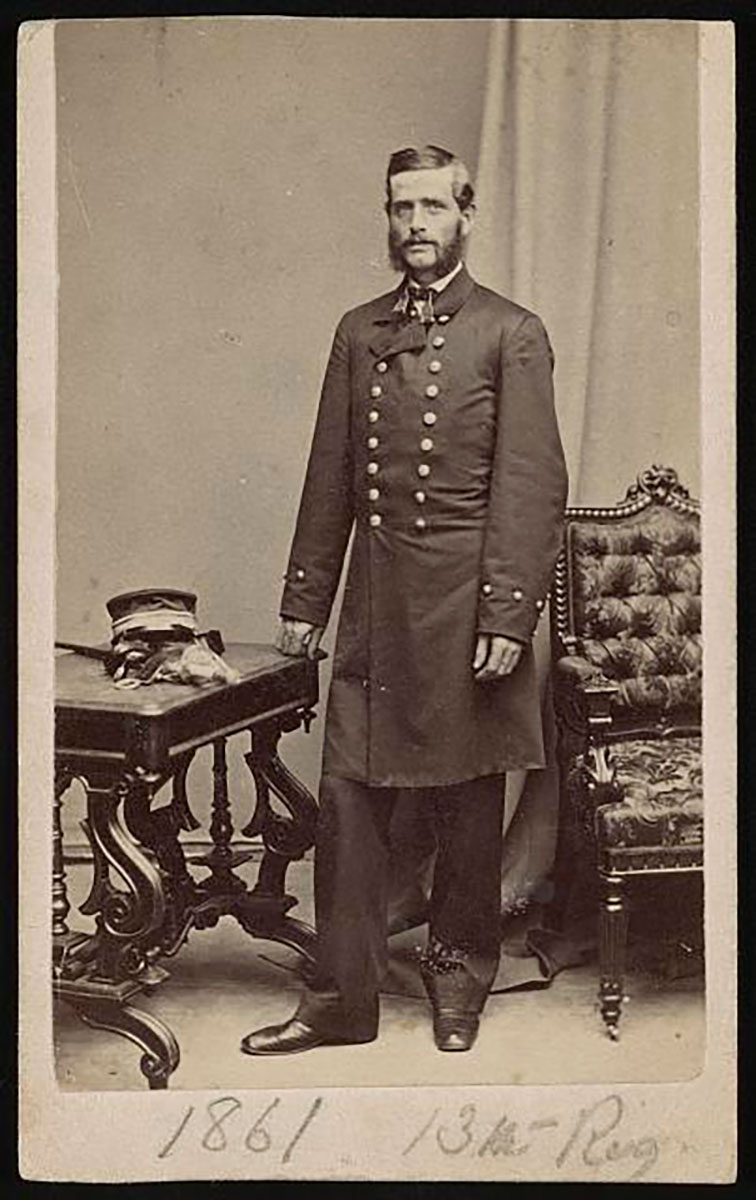

Dyer, born in 1836, entered the U.S. Navy in April 1862 after service in the 13th Massachusetts Militia (formerly the 4th Massachusetts Battalion of Rifles). His career, which saw service in the Civil War on several warships, would last through the Spanish-American War where he commanded the cruiser USS Baltimore in the Battle of Manila Bay under Admiral Dewey. He ended his Navy career at the Charlestown Navy Yard near Boston and passed away in 1910. He had been promoted to admiral during the last years of his career.

The Battle of Mobile Bay was the largest naval battle of the Civil War. It closed the city of Mobile to blockade runners for the rest of the war, trapping several of those ships in the port. Mobile itself, would not fall until April 1865 after the Union assault on the Fort Blakely and Spanish Fort fortifications on the east side of the bay. This Union victory, along with the fall of Atlanta in early September 1864, the Battle of Third Winchester later that month and the Battle of Cedar Creek in October, gave President Abraham Lincoln the military wins that he needed to secure his re-election in November. Mobile Bay also created the first four-star admiral in U.S. Navy history, David Farragut, who became arguably the most famous flag officer of the Navy in the entire war.

Any relic from this battle would be highly cherished but a flag from any of the warships involved would undoubtedly rank at the highest level of collectability, and this boat flag from the USS Metacomet is right up there. Even more so for its value was the probability that it was also used to fly over the CSS Selma after its capture."

Greg Biggs

Military Historian, Clarksville, TN

October 19, 2025

The flag is a national treasure. It is worthy of our Smithsonian. Mr. Biggs actually had this flag in his physical possession close to a year before sitting down to write his critically thought-out document. This document passes to the buyer. [pe] [ph:L]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

CLICK HERE FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About THIRTEEN STAR U.S. NAVY BOAT FLAG FOR THE GUNBOAT U.S.S. METACOMET

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Selection Of Unframed Prints By Don Troiani »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

Large English Bowie Knife With Sheath 1870’S – 1880’S »

Imported (Clauberg) Us Model 1860 Light Cavalry Officer's Saber »

featured item

A GROUP BELONGING TO CAPTAIN TO MAJOR DAVID SCHOOLEY

Battery M, Second Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery (112th Pennsylvania Volunteers) was recruited by Capt. David Schooley, July and August 1862. It was known then as Schooley’s Independent Battery. Please click on this link (ABOUT « David Schooley's… (1268-550). Learn More »