site search

online catalog

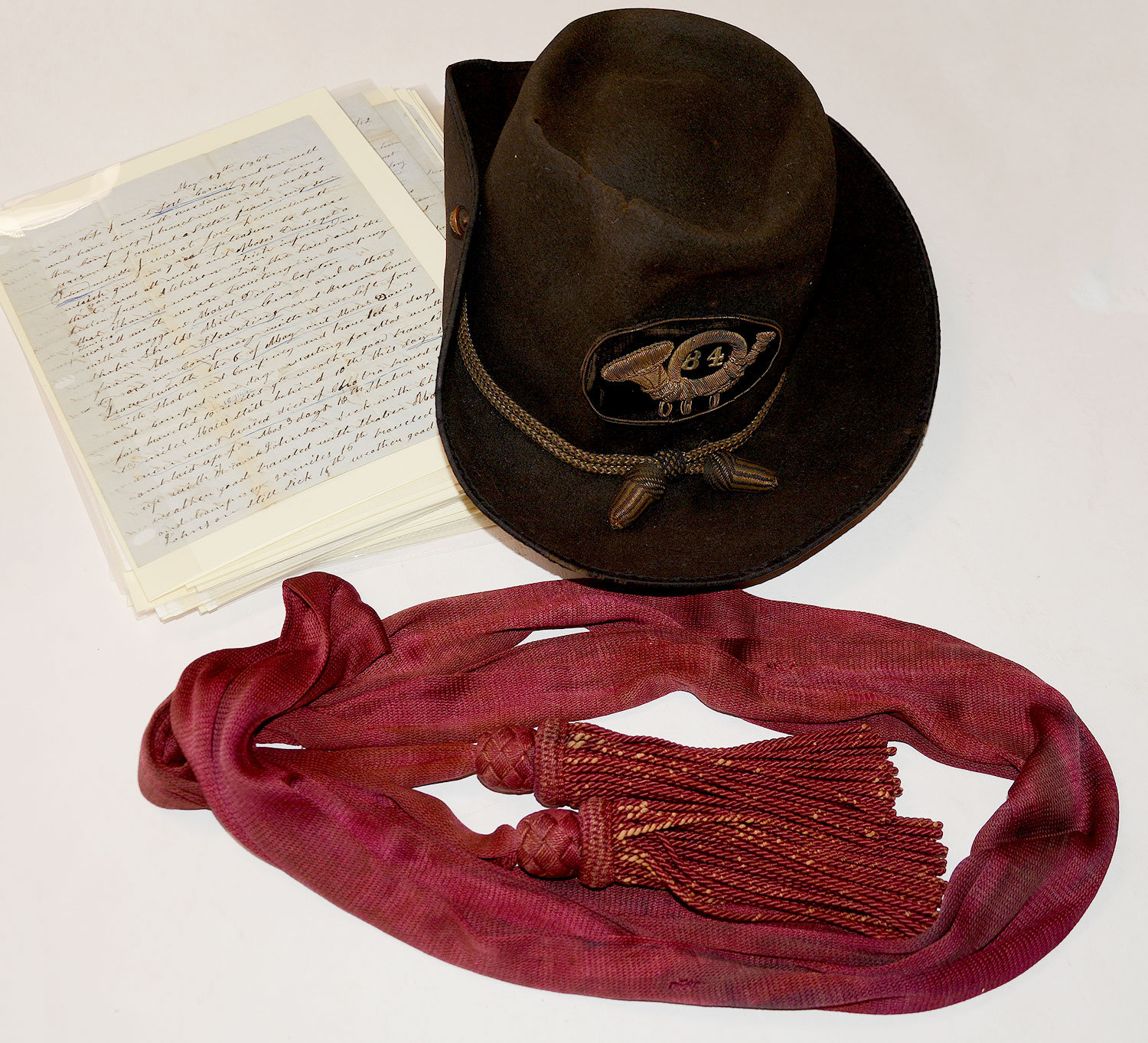

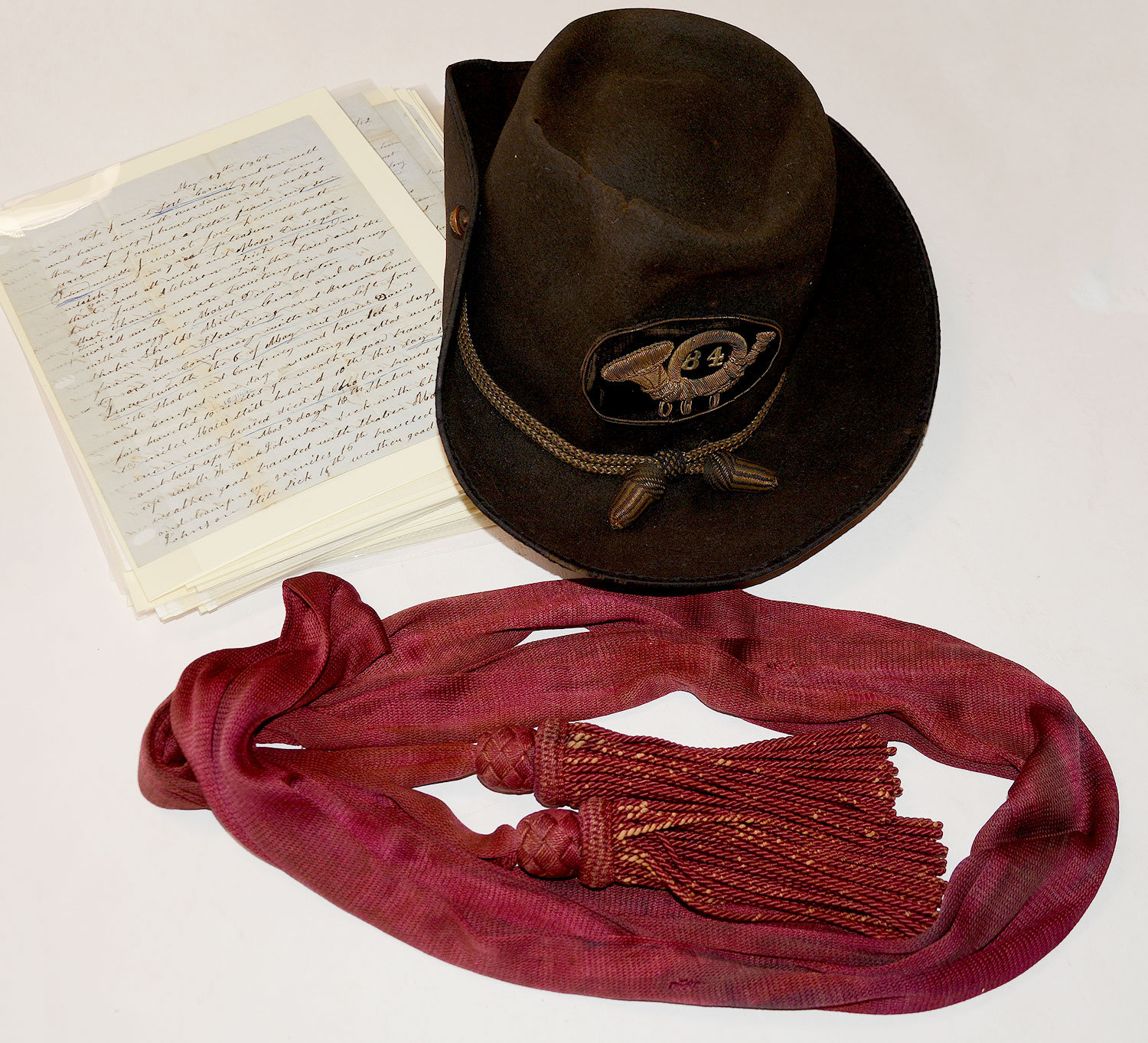

BULLET STRUCK HAT, OFFICER’S SASH, AND LETTERS OF CAPT. MOSES W. DAVIS 84th ILLINOIS, DIED OF WOUNDS RECEIVED AT STONES RIVER

Hover to zoom

$16,500.00 SOLD

Quantity Available: None

Item Code: 2025-301

Capt. Moses W. Davis, Co. D 84th Illinois, was wounded in the head and arm at Stones River (Murfreesboro) December 31, 1862, and died of his wounds January 20, 1863, at Elizabethtown, KY, while trying to reach home. The grouping consists of his impressive bullet struck officer’s hat, his blood-stained sash, and sizeable group of 35 letters. The latter includes courtship letters he wrote his future wife from the gold fields of California in the early 1850s, with accounts of his life there, a later letter written while prospecting in the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, and wartime letters including details of camp life and campaigning. Also included are a last letter to his wife from a Nashville hospital before he left for home, a telegram from a fellow officer at Elizabethtown telling her to come quickly, letters of condolence and an account of his last days, along with a touching short note written to him while in the army by then seven-year-old daughter Maggie, wanting to see him, praying for his safety, and mentioning their newest addition to the family, a baby brother Albert, and asking him to come home.

Davis’s hat and sash are accompanied by a note identifying them written by Davis’s granddaughter, who also made some pen annotations in the letters. The hat is black, with a 3-1/2” brim with ¼” grosgrain binding. The crown is about 6” tall, with the top pressed in slightly. It carries a regulation black and gold woven officers hat cord with acorns in place. The wearer’s right brim is turned up and in place by a small General Staff button. His embroidered bullion officer’s hat badge is in place, having a dark blue velvet ground, metal stiffener, and two loops secured on the inside by two leather wedges. It is 3-3/4” wide, with the top edge and wearer’s right edge bent back slightly, but with the jaceron wire in place. The gold embroidered hunting horn shows some oxidation or rubbing to a silver gray on high points. The regimental number consists of two false-embroidered gilt brass numerals, “8” and “4” with some oxidation to gray. The interior is very good, with the underside of the top showing some signs it may have had stiffener glued in at one point that was removed for comfort, but the 2-1/2” wide black sweatband is complete and in place. There is a small ½” diameter hole on wearer’s left about 2” up from brim and an oblong tear on top front edge of the crown on the wearers right, with no fabric missing, the tear measuring about 2-1/2 along bottom and 2” along top. There is a possible blood stain along lower edge toward rear on wearer’s left. It looks as if something struck him from above on the right and exited on the lower left, likely giving him a scalp wound.

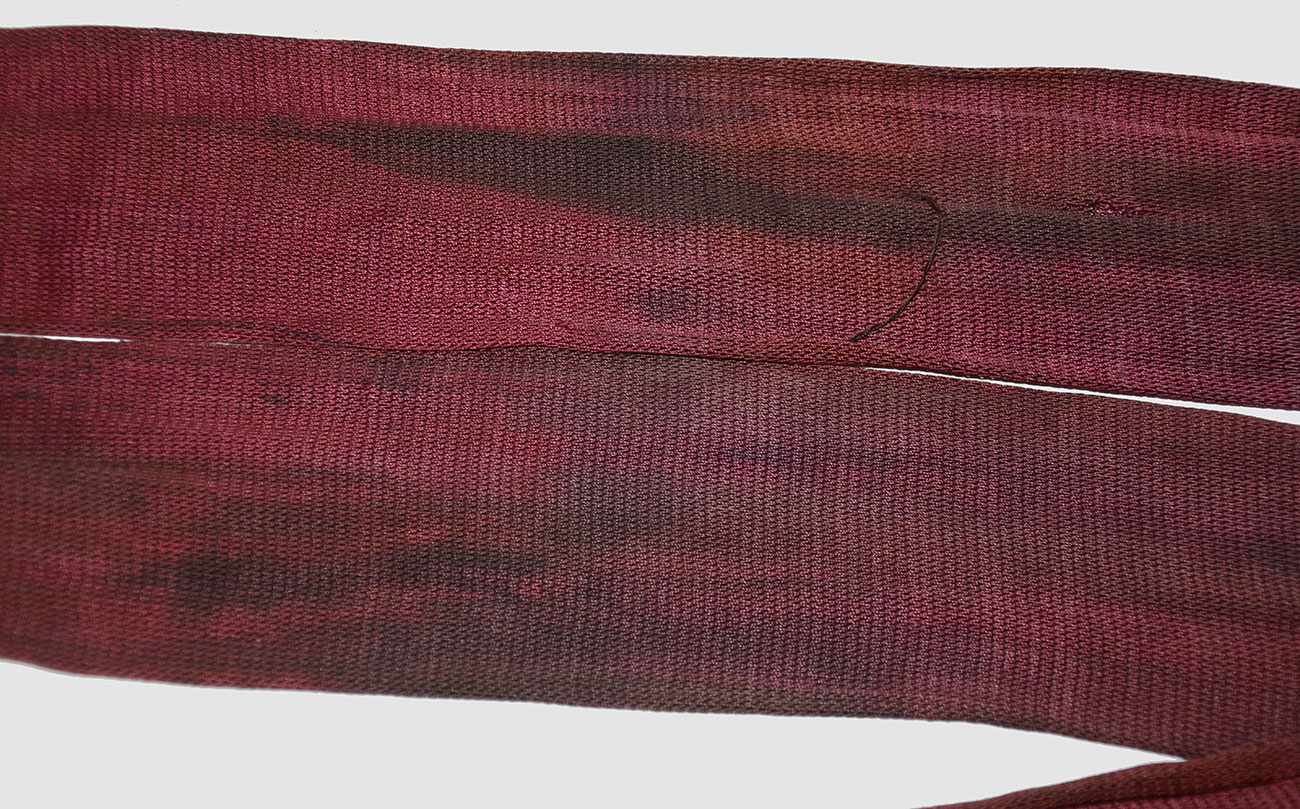

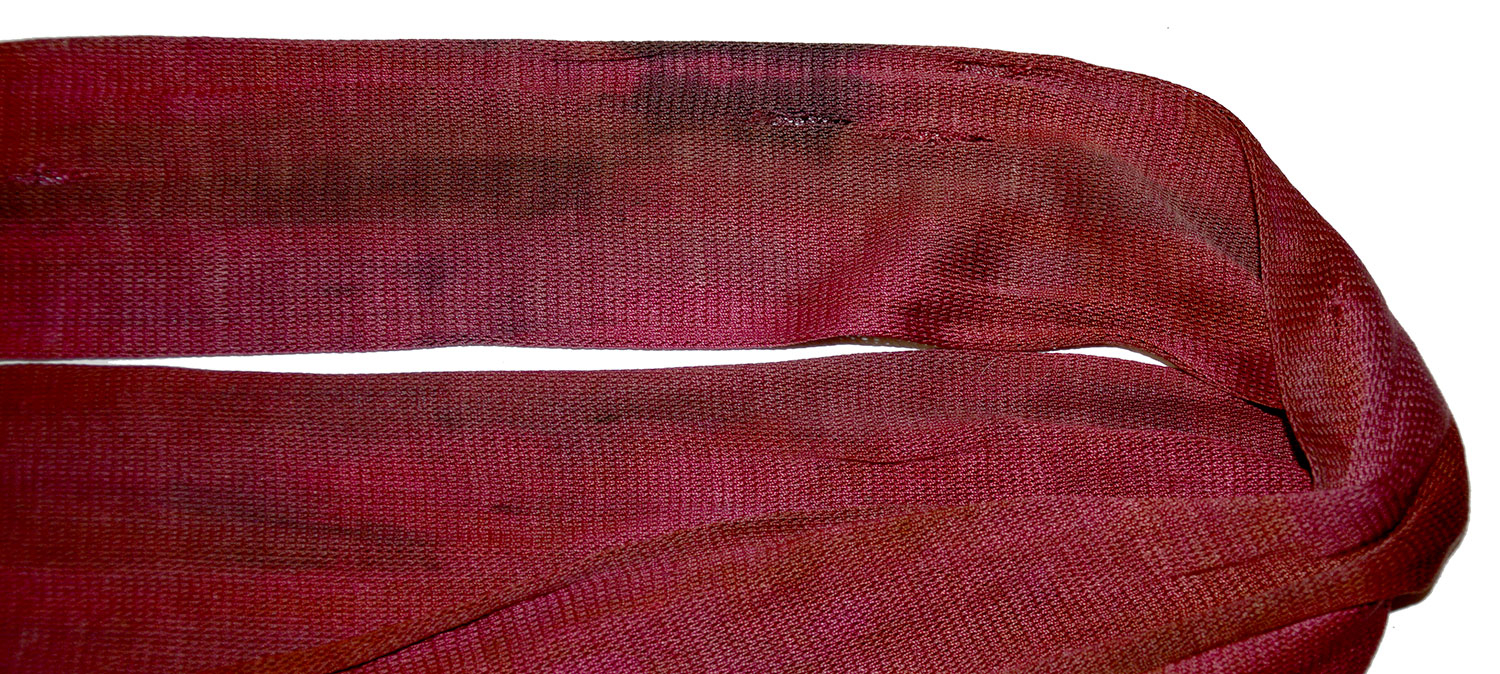

His officer’s sash is the regulation silk with turk’s-head knots and tassels, crimson in color, now oxidized toward maroon/purple, in solid shape with just some light wear to the tassels and 3 or 4 short runs to the fabric that only affect one side of the folded sash. It measures 3” wide (folded lengthwise,) and is about 112” long including 6-3/4” knots and tassels at each end. There are a number of dark stains said to be bloodstains by the family note and probably are. We have not tested them for blood, but they certainly look it, and he is recorded as having been wounded in the arm as well as the head.

Born in Tennessee in 1825, Davis was living with his family in Brown County, Illinois, by the 1840s and had a taste for adventure. He served in the Mexican War, serving as a private in a company commanded by Captains W.A. Richardson and G.W. Robinson, Company “E,” of the “1st Illinois Foot Volunteers,” enlisting at Alton, IL, June 26, 1846, to serve twelve months and described as 5’9” tall, of dark complexion, with hazel eyes and black hair, and a farmer by occupation. The regiment reached Texas in August and was part of Wool’s division and saw action at the Battle of Buena Vista. He was discharged at the expiration of his term of service, at Camargo, Mexico, on June 17, 1847.

He returned home to Brown County in time to be included in 1850 census as a laborer on the family farm, living with his parents and five brothers and sisters. This was officially “enumerated” in August, but a May 29, 1850, letter in the group, written from Fort Kearney by future brother-in-law George Adams indicates Davis was “Captain” of a group of eight wagons that had made their way from Fort Leavenworth. Four detailed letters from Davis himself, addressed to Winifred Adams, dated January, May, and September 1852, and February 1853, detail their long-distance courtship, living in small cabin with fellow miners on the “very verge of creation” in California, his work in the mines and his plans to return upon selling out a good profit. He apparently did so: the pair married back in Illinois in June 1853, where the 1860 census picks them up: he as a carpenter, age 34, she at age 24, with daughter Margaret age 5, sons George, age 3, and Guy, nine months. A Maggie Adams living with them and a school mistress we presume to be a sister or relative of Winifred. His wife could likely have used the company and help. A February 1860 letter to Moses from brother-in-law George, then in New Orleans, indicates Moses was thinking of heading west in the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, and a Sept. 10, 1861, letter by him from Chicago Creek, Colorado, shows he did so. The couple also welcomed another baby at some point in 1861, a boy they named Albert.

By mid-1862, however, he is back in Illinois and raising a company for the war that would become part of the 84th Illinois under Col. L.H. Waters. A July 1862 letter from Waters directs him to go into camp with his men at “Camp Butler,” and in passing refers to competition from other colonels trying to get enough men to muster in: “I should very much like to know who it is that is working to ‘hook’ your Co. from me.” The regiment was officially organized in August at Quincey, IL, and an Aug 17 letter (2pp ink) from Dixon at “Camp Quincey” refers to the baby being sick at home, his own sickness from diarrhea, waiting for the mustering officer, paymaster, uniforms for all of his men, etc. The regiment was officially mustered in on Sept. 1 and letters of Sept. 3 and 19 (3.5pp ink and 2pp ink) are also written from “Camp Quincey,” describing difficulties getting paid, camp duties and camp routine, etc., along with a visit from his son George and hopes his wife will bring the other children for a visit, though he does mention a mumps outbreak.

The regiment was ordered to Louisville, KY, on Sept. 23 to counter Bragg’s “Heartland Offensive” and Sept. 26 letter (2pp ink) from Louisville says they had arrived that morning after being cooped up in the cars for 48 hours and are putting up tents. 150,000 troops are said to be in the area and Bragg 20 or 30 miles away with 30-60,000, “so there is is no apprehension of an attack on this place now. Dear wife I did not realized the sacrifice that we were making until I come to start south But we are conscious that our cause is most just and the God of battles is on our side. I feel to trust that he will take care of us and spare me to return to you …” He also thanks her for sending picture with the children, and has sent one of himself.

An Oct. 1 letter (3.5pp pencil) is likely from Louisville, mentions camp news, and reports on sickness but notes things are looking serious: “We thought we were soldiering at Quincey, we are into it now…” but notes “the 84th is a Crack regiment and we are being put through- as for Capt. Davis he came here to do his duty…” It concludes with, “we are just ordered to move May the Lord Bless and protect you and our children and bless our country and cause…” This was at the beginning of Buell’s pursuit of Bragg in Kentucky from Oct. 1-16, which culminated in the Battle of Perryville on Oct. 8. The regiment was credited with that battle, but its division was not engaged, reporting no casualties. Dixon’s letters pick up again with a series of five letters detailing campaigning and marches first in pursuit of Bragg and then in return to Nashville (which essentially cost Buell his career:) 10/15/62 (4pp pencil. Some rubbing, mostly legible) Recounts marching and skirmishing most every day. “A terable battle is pending it may be in a day or two or a month off. He reports hard times as might be expected with so many troops, has not been in a house since left Louisville, poor water and food, etc. He also retells being arrested and deprived of a his sword for a day, “for Easing myself too near our Brigadier general’s tent…” which he thought was untrue, foolish and made the Colonel and the regiment “hopping mad.” He later writes again, noting the brigade is in the advance and has lost about ten killed or wounded. A 10/23/62 letter from Rockcastle River (4pp pencil, light but legible) also tells of rough conditions; a 11/1/62 letter from Columbia, KY (2pp ink” says they have marched about 90 miles, on half rations, no tents, and says he has noted only about 30 miles of good country in the 300 the have traveled in Kentucky, noting the paucity of schoolhouses, conditions of the march, lacking tents and building brush shelters against the snow. He hasn’t seen a newspaper for months or heard a prayer meeting or sermon- “It is perfectly awful- the immorality and wickedness of the Army…” wishes people at home would pray for speedy & honorable termination of this most unholy war… and has been under fire three times and once within 400 yards of Rebel cannon and their balls tossed the corn stacks over their heads. He thinks generals are mismanaging things, but it is only his to do his duty. A 11/5/62 letter from Glasgow KY (2pp ink) notes there have been no sabbaths, no rest, and that he has 81 men, 10 of whom are unfit: “I am truly sick of this stile of soldiering- but not tired of serving my country I don’t want to sheathe my sword until the last Rebel lays down his gun.” A 11/15/62 letter from Camp Silver Spring, TN (4pp ink,) notes they are in the presence of the enemy again and that he is anxious to hear cannon again: “Soldiering without a little fighting don’t pay. There is no fun in it unless we are in the vicinity of the enemy…”

The regiment was back near Nashville by Nov. 28 when he writes a lengthy 9-page letter to his wife (ink) giving her news of local men, notes the regiment has been reduced in number by the weak having died or been discharged, “the army is no place for a man with any physical defects,” records drill and picket duty, describes his quarters, says he is constantly busy with camp duties but can’t stand to be idle, mentions he lost her likeness and wants another, and makes reference to an uncle and aunt not liking him, but that they can “kiss my Royal Magnolia A_s_” This is followed by some talk of politics and religious reflection that he has avoided all “camp vices” and maintains good discipline among his men and is well liked. This letter was followed an equally lengthy one four large pages, (ink) to “friend Asa,” which has extensive details of the Perryville campaign starting with their trainride from Quincey in open cars like cattle, etc., noting their inaction at Perryville and the general consensus that Buell had the advantage in the battle and let Bragg get away, noting the progress of their march back to Nashville, along with picket duty and “more or less skirmishing every day…” A 4-page letter to his wife of Dec 7 includes an insert with notes to his children (light but legible.) A 2-page letter of Dec. 17 (ink, light but legible) gives some camp news, notes of picket and foraging, and that he has a cavalry overcoat – the only one in the regiment (noteworthy as double-breasted, fitted with a longer cape, etc.) A Dec 19 letter (4pp ink) continued on Dec. 21 (in another 4pp sheet) to a Mr. Stone adds some details of camp and picket duty, a description of Nashville, etc.

Davis’s last letter to his wife before Stones River is dated 11:00 P.M. Christmas Eve, in which he calls himself the lucky man of the 84th, having just received pictures she sent of herself and the children. He notes some noise in camp from celebrating, but also that they had expected to march that day, having been “to pack everything this morning put three days grub in our Haversacks & 2 in our wagons, but we are yet in camp. I expect we will be off in the morning.” This is followed by word of a fight at Gallatin, about 15 miles away, with reports they had driven the enemy and taken 150 prisoners.

Dixon’s last letter to his wife was written from Hospital No.14 at Nashville on January 5, 1862. He notes that he had written from the battlefield but the lines of communication had been cut. He reports being comfortably situated, arriving after an all night ride in a wagon: “We have had a terable battle and have driven the Enemy back. The fight lasted five days I was wounded in the first engagement Dec. 31st about noon in the head & left arm. You must not worry about me for I am doing first rate. My regiment was cut all to pieces. Lost more than half the men we took in to the fight…” He mentions going into the fight with 39 men and coming out with 22, and follows it with a list of casualties, praise that was given to the brigade by Rosecrans and a defiant note: “I would not take the best Farm in Ill. for my place in the 84. You may think this all gas or loud talk but it is the truth. Every word of it….”

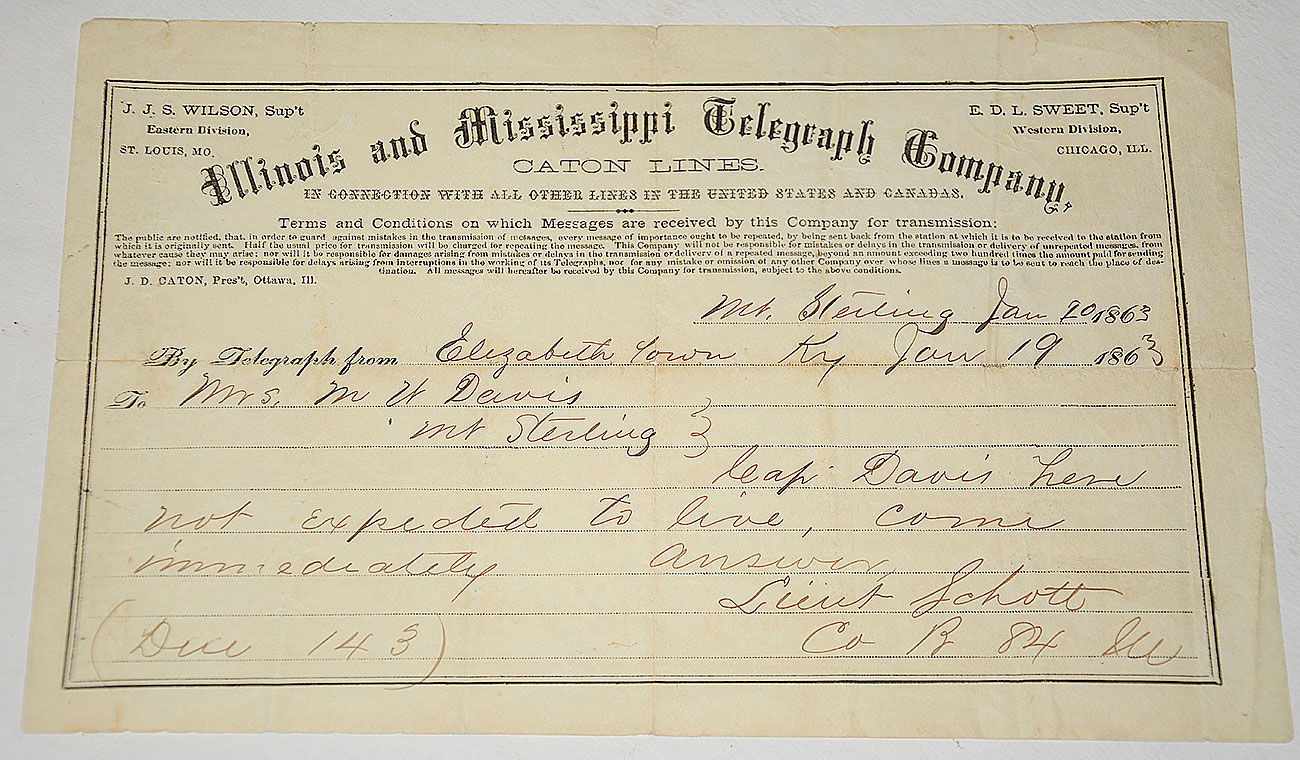

This is followed by a telegram to Davis’s wife from Elizabethtown, KY, dated Jan. 19 reading, “Cap Davis here not expected to live. Come immediately. Answer Lieut Schott Co. B 84 Ill.” This is certainly Lt. L.L. Scott of Company B, who wrote her the next day, saying that he had hoped to see Davis safely home, but that he had become to feeble to travel and Scott’s own wounds prevented him from nursing him, but feels he has “provided the Cap with all the comforts I can and now must hasten to my own dear wife and children hoping you will find him much better when you arrive…”

Davis died the same day that Scott wrote the letter. Scott only heard of it later and is apparently the writer of a four-page letter to Mrs. Davis on Feb. 22, apparently missing a final page or two, but recounting their stay in the hospital at Nashville (where Davis was visited by his brother James) and their trip to Elizabethtown where Davis became too weak to travel or reach the railroad by horseback in the snow. Letters of condolence to Mrs. Davis include one from her brother and another from Col. Waters: “In the terrific battle of 31st he was at his post cheering and encouraging his men until he was wounded and carried to the rear. Badly wounded as he was, he could not forbear visiting the regiment the next day and was received with cheers from all.” There is also a lengthy letter written to Davis by a Sergeant who did not know he had died on trip home, written on paper torn from a larger government form, and is a bit light but can be made out. The Colonel’s letter is fully legible and complete, but torn on fold lines.

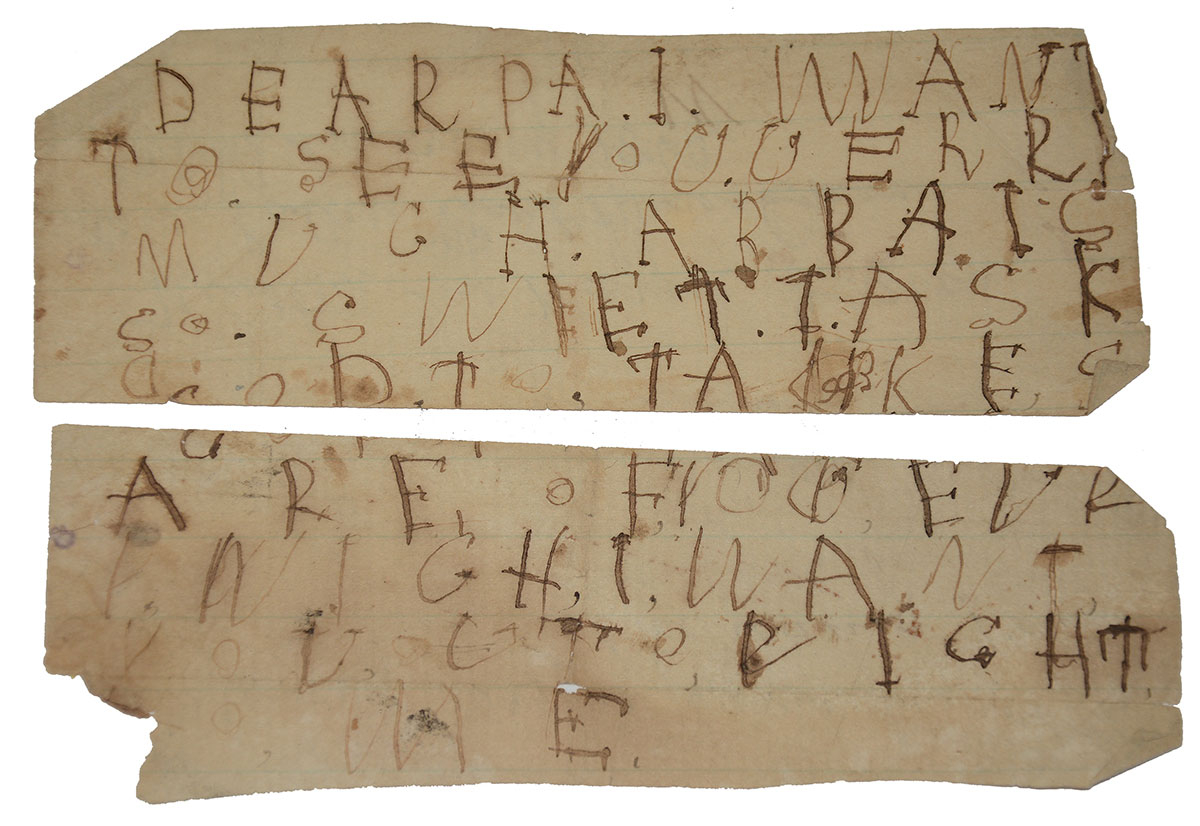

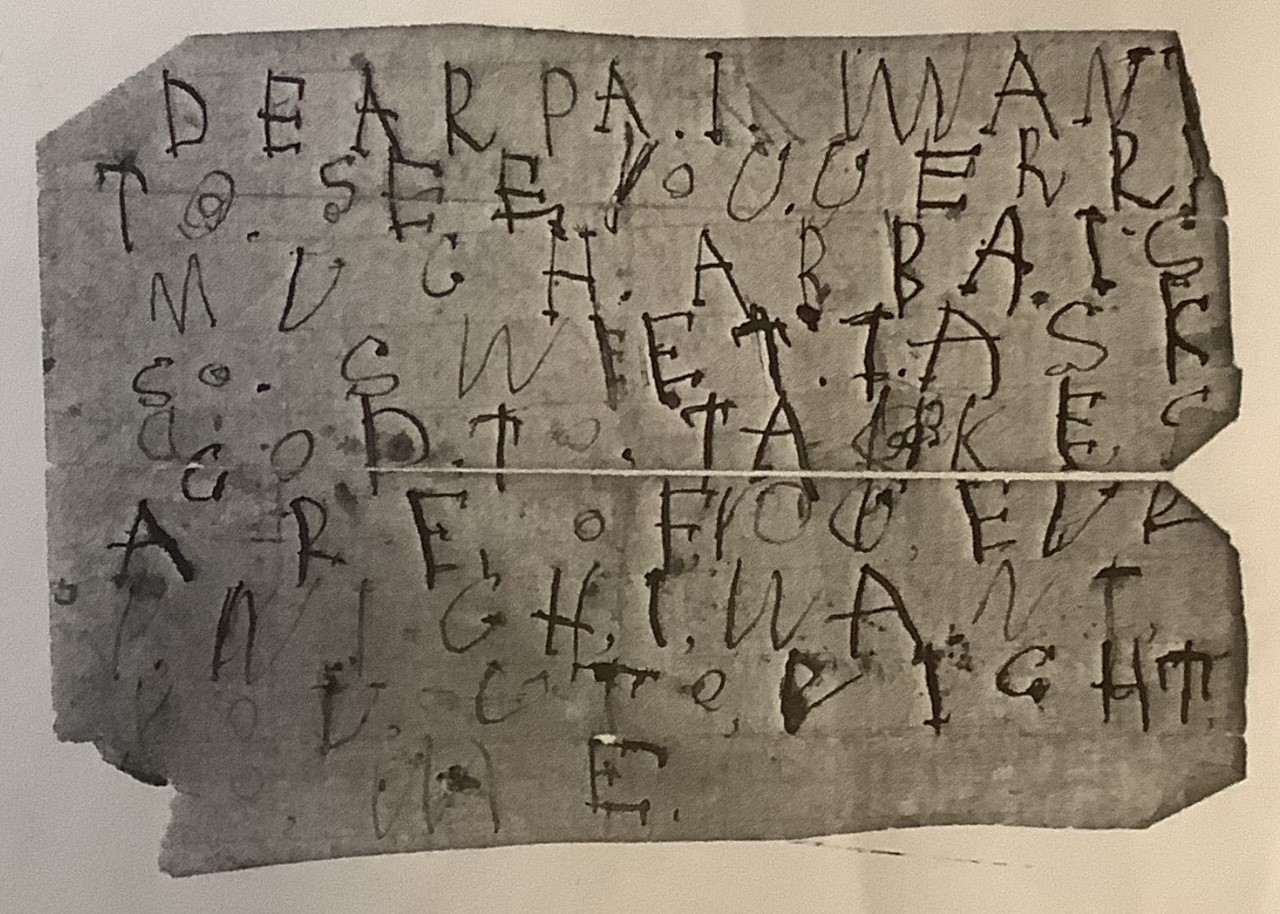

There are also a few stray notes in the group, two pencil notes apparently by Davis torn from a notebook, a resolution of condolence to Mrs. Davis by a Mt. Sterling masonic lodge, a later note to her from Col. Waters regarding the regiment’s flag, etc. Perhaps the most affecting piece, aside from his last letters, is a note torn across a fold line but complete, penned in all capital letters by his daughter Maggie reading: “DEAR PA I WANT TO SEE YOU VERRY MUCH. ABBA IS SO SWEET. I ASK GOD TO TAKE CARE OF YOU EVR[Y] NIGHT. I WANT YOU COME RIGHT HOME.” The word “abba” caused some puzzlement at first, but an elegant solution was inspired by Mr. R. H. Hoffman (credit where credit is due) that this is 7-year-old Maggie’s transcription of two-year-old brother Guy’s pronunciation of baby brother Albert’s name.

This is a wonderful set, historic and tragic, with eye appeal in the hat and the sash, personal history and details in the letters, more room for research and background, and a good deal more detail in the letters than we can give. [sr][ph:L]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

CLICK HERE FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About BULLET STRUCK HAT, OFFICER’S SASH, AND LETTERS OF CAPT. MOSES W. DAVIS 84th ILLINOIS, DIED OF WOUNDS RECEIVED AT STONES RIVER

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Selection Of Unframed Prints By Don Troiani »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

British Imported, Confederate Used Bayonet »

Scarce New Model 1865 Sharps Still In Percussion Near Factory New »

featured item

MAMALUKE SABER MANUFACTURED IN ENGLAND

Manufactured: England Maker: William Harvey Year: 1840 - 1850 Model: Mameluke Size: 30.25 Condition: VG Wonderful Mamaluke Saber manufactured in England. Most likely for a British officer but possible it was imported to the US market. … (870-74). Learn More »