site search

online catalog

SUPERBLY DOCUMENTED AND WONDERFULLY MAKER-MARKED BY CASSIDY OF NEW ORLEANS CONFEDERATE SIGNAL FLAG CAPTURED AT FORT ST. PHILIP

Hover to zoom

$2,500.00 ON HOLD

Quantity Available: 1

Item Code: 1179-275

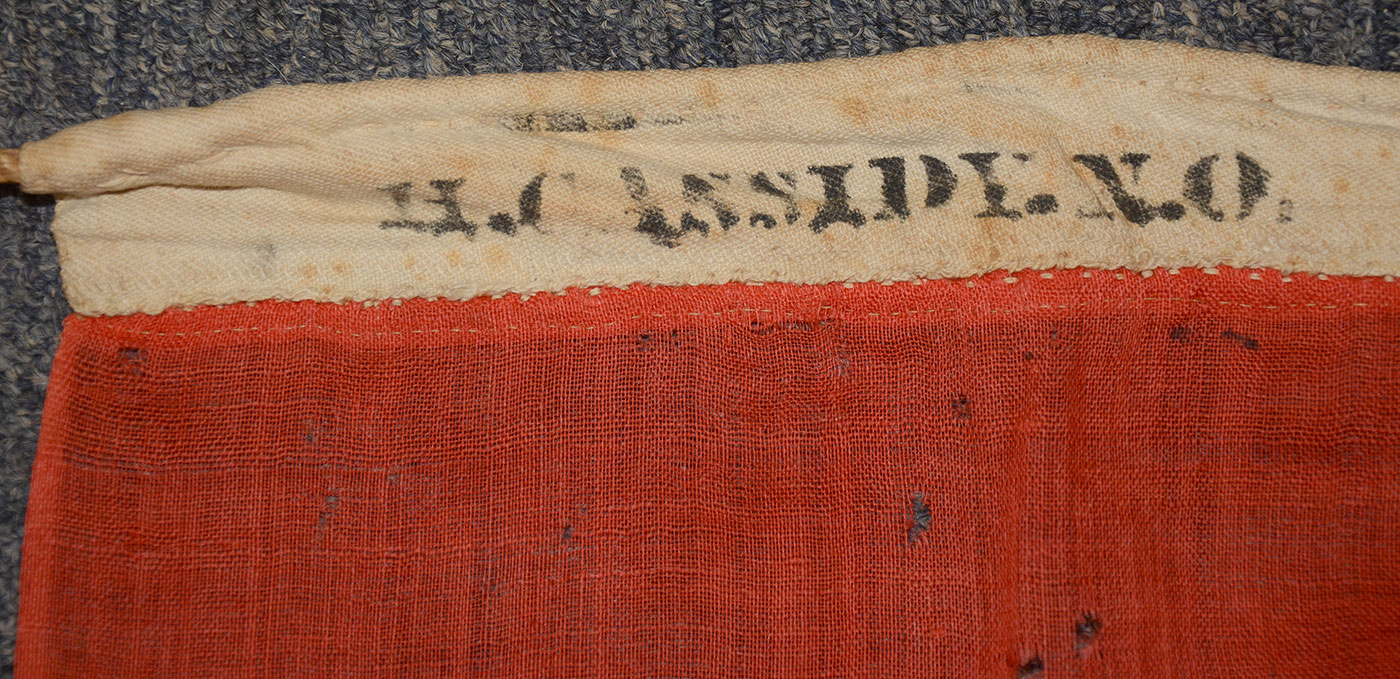

This is great example of a Confederate signal flag, taken from the “flag room” of Louisiana Confederate Fort St. Philip by Joseph Davis, then Hospital Steward of the 30th Massachusetts, which briefly occupied the fort after its surrender on April 28, 1862, in the wake of Farragut’s successful passing of the forts and the surrender of New Orleans, just upriver. The flag is in excellent condition, with just a few holes, and is clearly stenciled on the canvas hoist in black 1/2-inch letters, “H.C. CASSIDY. N.O.” indicating manufacture by Henry C. Cassidy, a former sail-maker in New Orleans who had gone into the tent, awning and flag business, supplying flags to many Confederate units and also working on contract with the states of Louisiana and Alabama. Marked examples of his work are, to say the least, scarce.

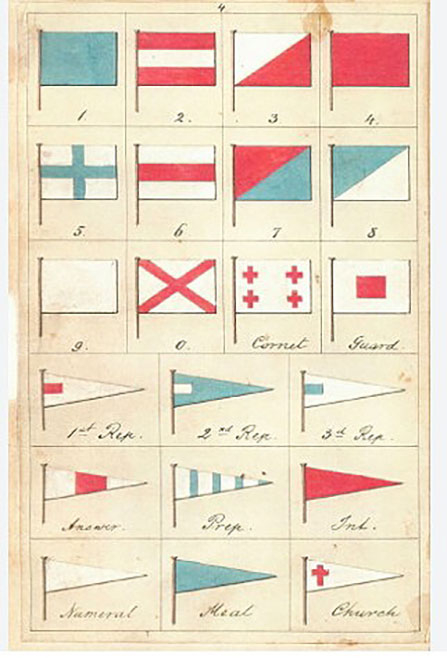

The flag itself is solid red and rectangular, indicating the number “4” in “Signals for Use of the Navy of the Confederate States” published in Richmond in 1861. We show the appropriate page from this manual. Based on the Rogers system of signal flags of the 1850s, in addition to other signal flags, flags with numerical designations from “0” to “9” were hoisted to produce a number corresponding to an entry in a code book for various instructions, directions, orders, formations, phrases, etc. The system was used by both the US and Confederate navies and in Confederate fortifications, albeit with various changes to the numerical designations to prevent the enemy from correctly deciphering signals- the Confederates using the solid read flag as a “4” in 1861 and the Union it to indicate “1” in 1864 for instance- or by using additional signals to indicate the numerical designations had shifted by a certain interval.

The flag is roughly 36 inches wide and 66-inches long overall, allowing for some shrinkage or stretching. This includes a canvas sleeve holding a hoist rope about 42 inches long with a loop at either end, the sleeve about 2-inches wide if laid flat and 1-1/2 inches with the rope. The body of the flag is red bunting, in two long panels each 18 inches wide, seamed lengthwise, 64 inches long, with fabric at the fly end turned under to give it a 1-3/4 inch hem to prevent fraying. The flag has strong color and is solid with a few holes that do not affect its stability or overall appearance. It was folded lengthwise at some point and there are matching 2 by 2-1/4 inch holes about 10 inches from the hoist, each about 2 inches from the center seam. On one panel there are a few smaller, 1-inch holes slightly below and about 5 inches beyond the larger hole, and a 1-1/2 inch hole about 3 inches below the seam and 9 inches from the fly end. None of these are particularly objectionable. The flag is substantially intact. The Cassidy maker’s stamp is very clear and legible at a distance. Please see our photos.

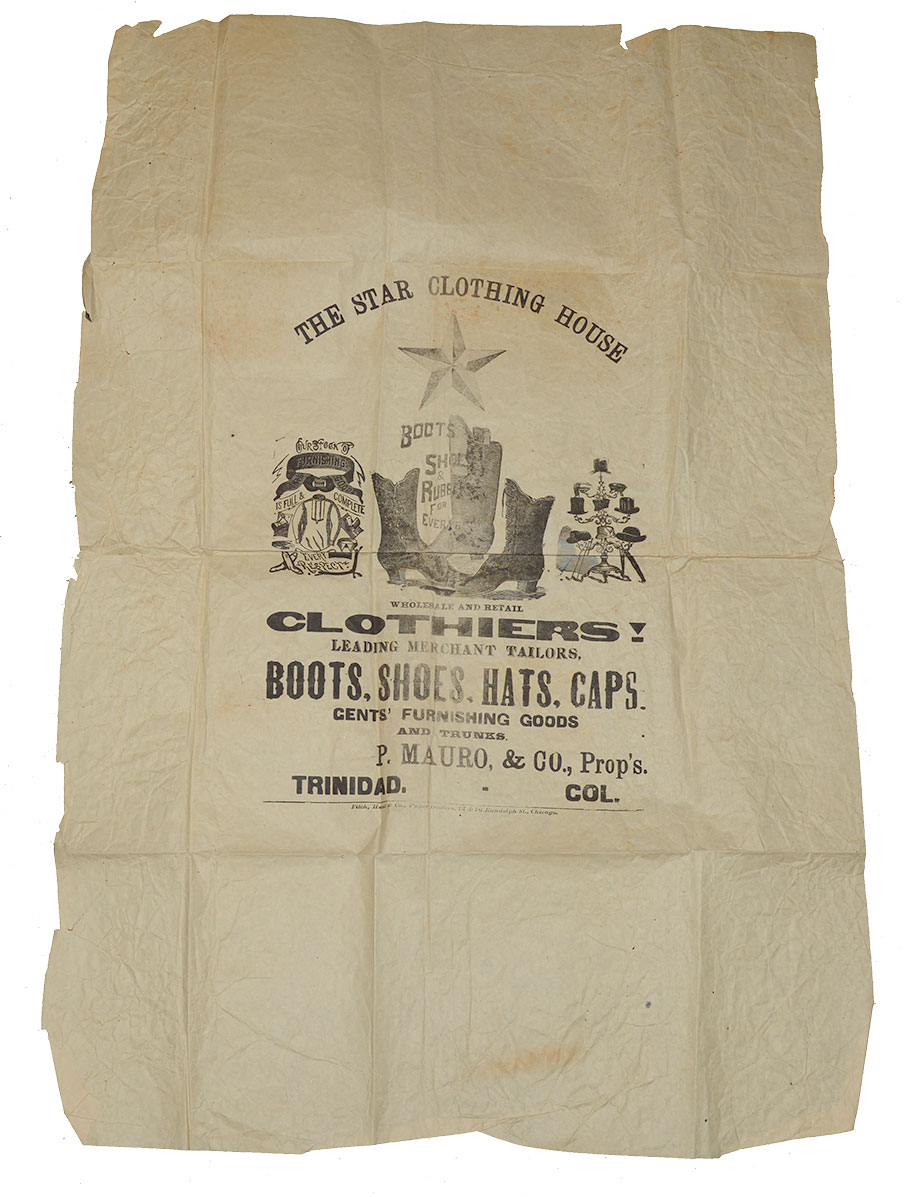

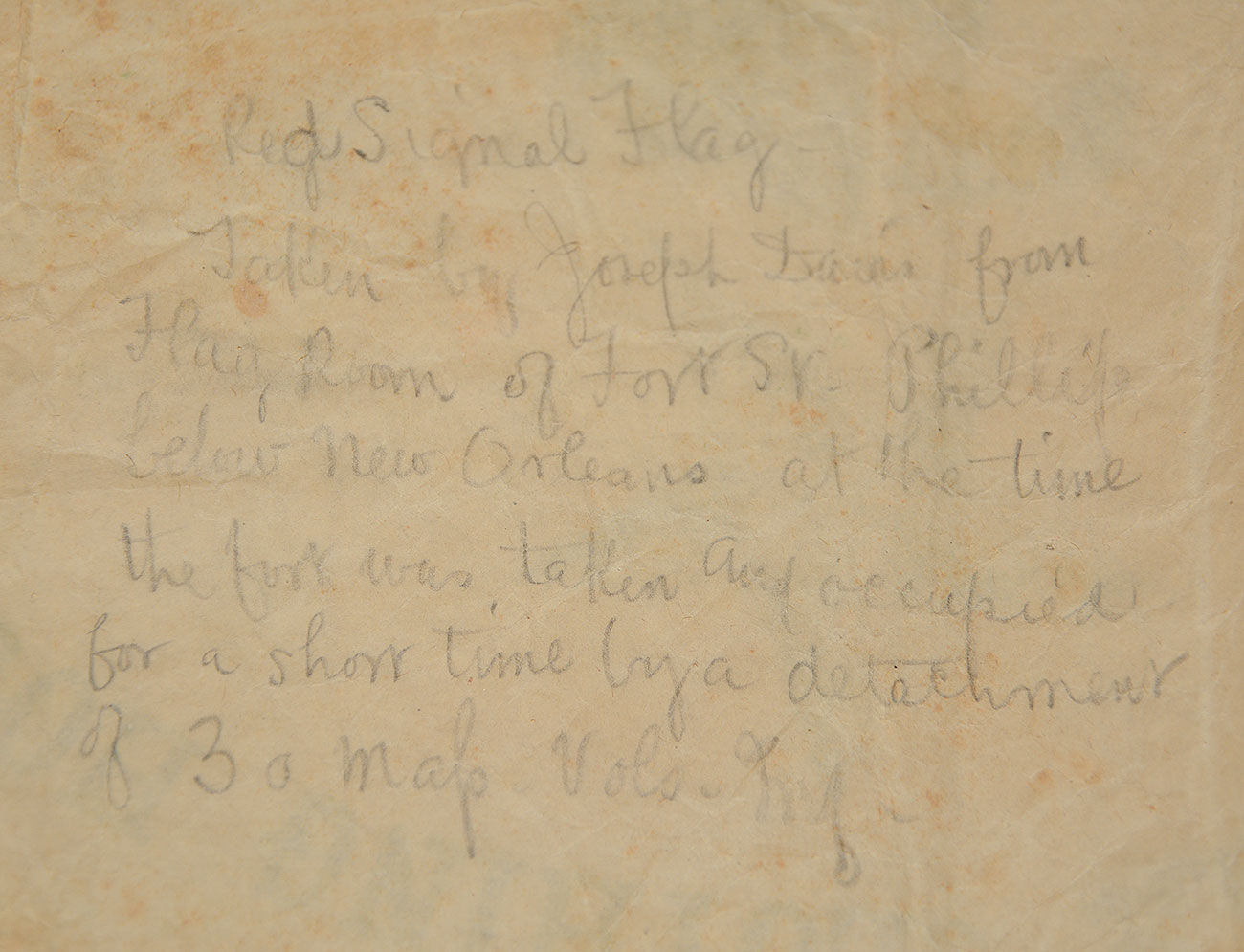

The flag comes with a correspondence among the flag’s finder, Ed Simmons of Glendale, Alabama, and David W. Gaddy, a scholar on the CS Signal Service, and their mutual friend, well-known collector and author Bill Albaugh. According to a signed letter dated 25 Sept. 1975 from Simmons, the flag was in a trunk of Davis’s belongings he had bought some years before in California. This fits with our own research, showing Davis died Dec. 28, 1926, in Los Angeles. Davis had also lived in Trinidad, Colorado, after the war and Simmons fortunately preserved the large sheet of wrapping paper from “The Star Clothing House” of Trinidad, Colorado, in which Davis had wrapped the flag and added a handwritten pencil note reading: Red Signal Flag / Taken by Joseph Davis from / flag room of Ft. St. Phillip / below New Orleans at the time / the fort was taken and occupied / for a short time by a detachment / of 30th Mass. Vol. Infantry.

Joseph P. Davis had enlisted in the 5th Mass at age 20 at Medford, MA, on 4/16/61 and mustered into Co. E as a private on 5/1/61, serving until mustered out 7/31/61. He then reenlisted on 1/4/62 in the 30th Mass as Hospital Steward, gaining a commission as 2nd Lieutenant of Co. E on 8/21/62, and then as 1st Lieutenant and Adjutant on 10/22/63. He was discharged for disability on 2/12/65. The regiment took part in Butler’s expedition to Louisiana and New Orleans and later saw extensive service in Louisiana before transferring with the 19th Corps to Virginia for service in the Shenandoah. He had gone west soon after the war, was recognized as an early pioneer of Colorado, and reportedly had lived in California for about two decades before his death there in 1926, leaving behind a son who was a “Hollywood investment broker” and oil company executive. Davis himself had an interest in genealogy and in history, likely accounting for his careful documentation of the flag on its wrapping.

Fort St. Philip had surrendered to U.S. forces on April 28, 1862, along with Fort Jackson, the two forts having blocked passage of Farragut’s fleet up the Mississippi to the target of New Orleans. They were subjected to bombardment by U.S. naval guns and mortars from April 18 to April 23, but remained active, at which point Farragut decided to simply force his way past the forts and deal head-on with Confederate naval vessels and other land batteries, which he did on April 24 with the loss of one vessel, destroying twelve Confederate ships in the process, reaching New Orleans on April 25 and compelling the city’s surrender. Union land forces under Butler, along with naval forces still in the area, in the meantime resumed bombardment of the two forts, which remained defiant, but capitulated on April 28, giving Davis the opportunity to acquire the flag before the 30th Mass moved on to New Orleans and then Baton Rouge.

This is a very scarce flag from the Confederate signal service, a rare branch of the Confederate military, boldly marked by a recognized Confederate flag maker, and well documented as used in a historic campaign. The forts had put up a good fight, but the Union victory there opened the way for control of the Mississippi delta and ultimately the entire Mississippi River with the fall of Vicksburg little more than a year later, splitting the Confederacy in two. This comes with a file of research material and a display card from the Texas Civil War Museum, from whose collections we obtained it. [sr][PH:L]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

CLICK HERE FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About SUPERBLY DOCUMENTED AND WONDERFULLY MAKER-MARKED BY CASSIDY OF NEW ORLEANS CONFEDERATE SIGNAL FLAG CAPTURED AT FORT ST. PHILIP

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Selection Of Unframed Prints By Don Troiani »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

featured item

VERY ATTRACTIVE DOUBLE CASED SIXTH-PLATE AMBROTYPES OF CIVILIAN AND CONFEDERATE SOLDIER IN A RARE UNION CASE

The relationship between the two men pictured is not known but no doubt they are either brothers or the same man at different points in his life. The left side ambrotype is of a seated man sporting a closely trimmed beard and mustache wearing a dark… (1138-1975). Learn More »