site search

online catalog

KADY BROWNELL’S SWORD! “THE HEROINE OF NEWBERN . . . THE COLORS SHE CARRIED SHE STILL KEEPS . . . AND THE SERGEANT SWORD WITH HER NAME CUT ON THE SCABBARD . . .”

Hover to zoom

$7,500.00

Quantity Available: 1

Item Code: 2025-299

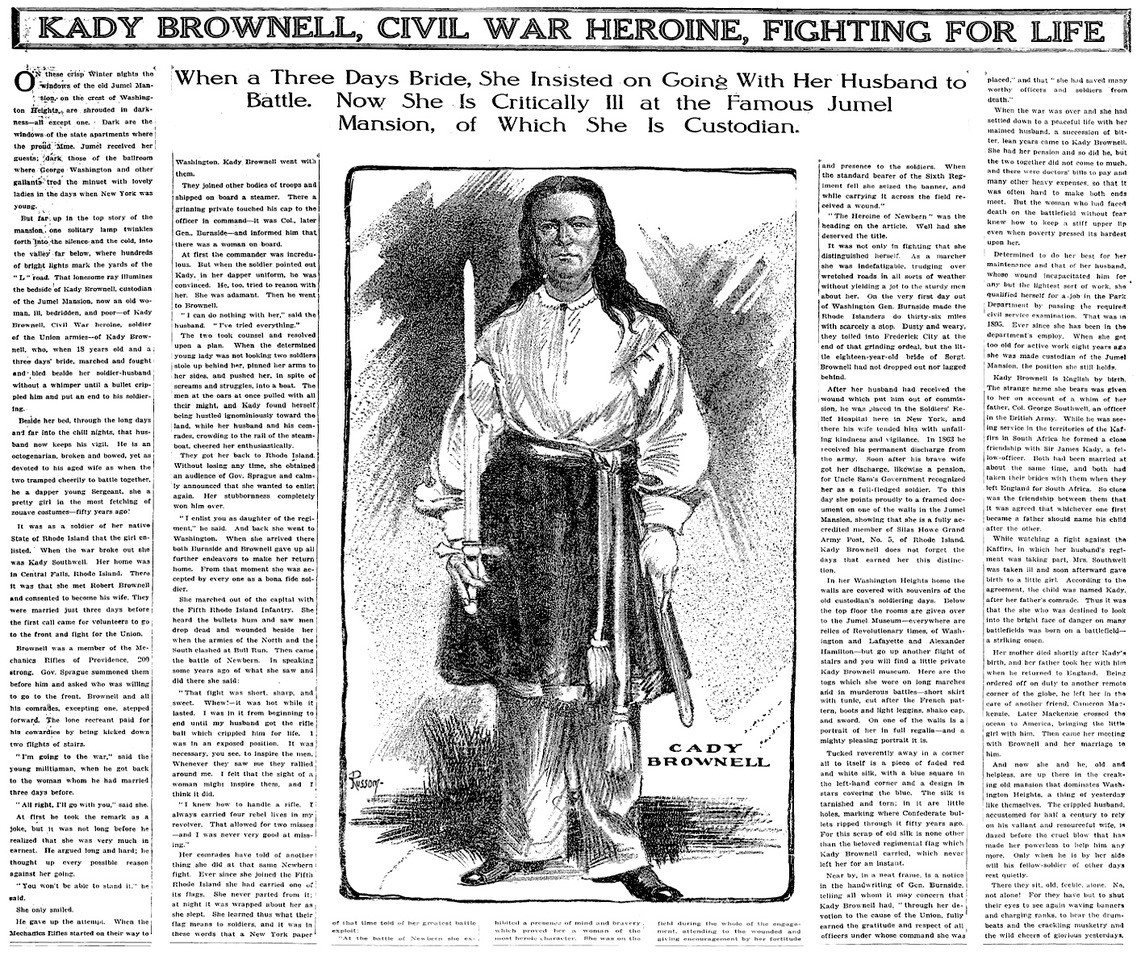

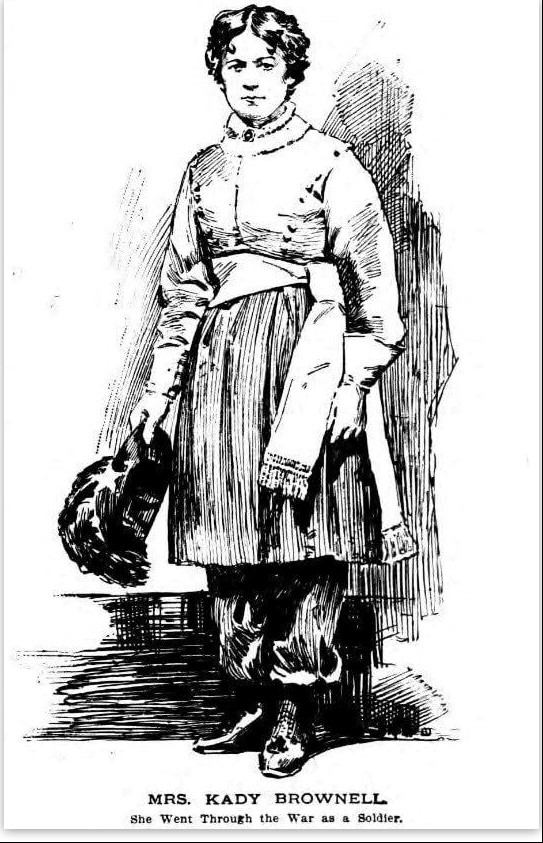

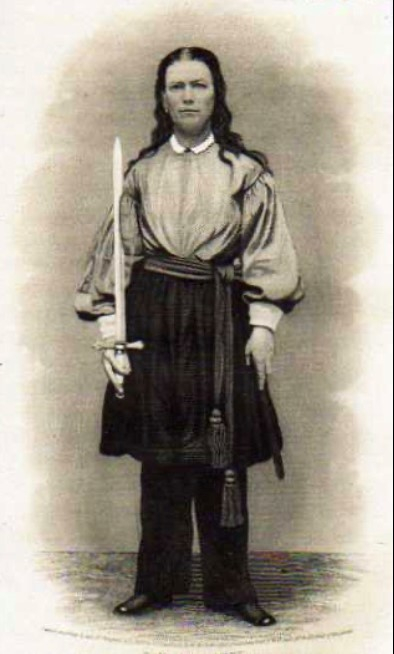

Kady Brownell was one of the colorful characters emerging from the Civil War who gained some notice at the time and a good deal more through self-promotion in the postwar years. She will be most familiar from a series of photos of her in semi-zouave, vivandiere-style garb she used for stage appearances about 1870, sometimes shown with musket and bayonet, and very frequently with this sword, which is crudely engraved on the scabbard mounts with her name (and regiment,) as mentioned by Frank Moore in his 1866 compilation “Women of the War,” quoted in our title. The sword was mentioned in Clarke’s 1891 history Co. F 1st Rhode Island Detached Militia: “She wore a uniform somewhat similar to that of the regiment, and was proficient in the use of a revolver and a short, straight sword, that she always wore suspended at her side.” And, it is appears in newspaper articles, including a 1913 New York Times article that mentions its display in her private “museum” in the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City, where she and husband Robert had been custodians since its public opening 1907. More recently it was in the collections of the Texas Civil War Museum, from which we now offer it.

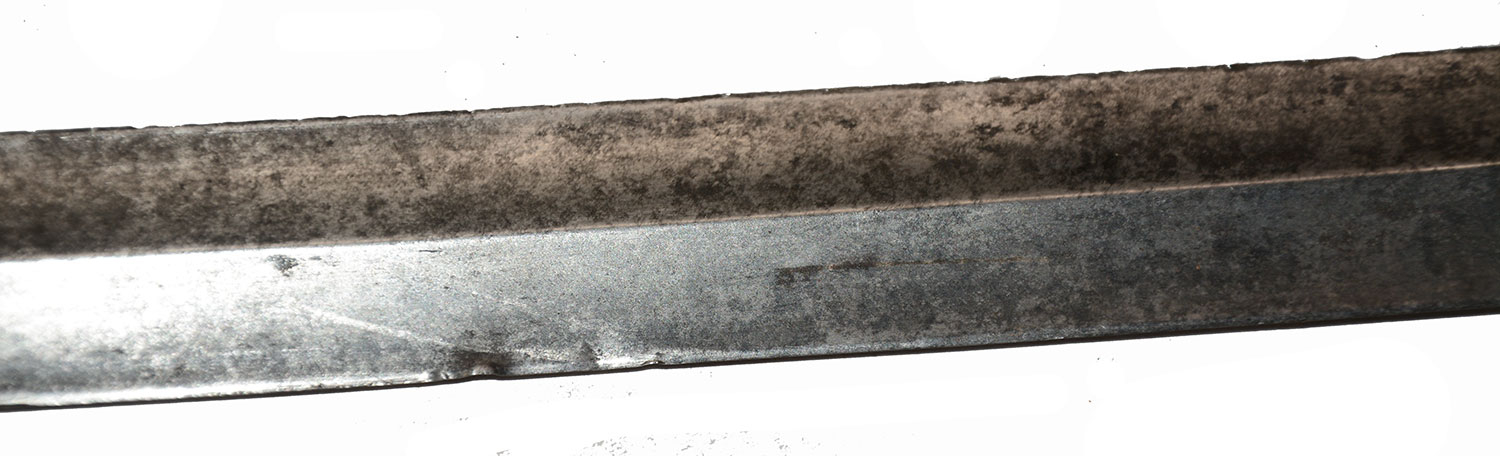

The sword is an 1850s militia non-commissioned officer’s sword, measuring 30-inches overall with a 23 ¾ inch robust blade that is straight, double-edge, spearpoint, and rather wide at 1 ¼ inches at the guard. It has a prominent median ridge for 17 inches from the guard with concave fullers on either edge giving it almost a flattened diamond cross section before tapering out, with the last 6 ¾ inches of the blade oval in cross section. The grip is ribbed, white bone, now cream colored, oval in cross-section with a slight swell. The pommel is a brass knight’s helmet with plumed crest. The brass crossguard is flat, cruciform, flaring toward the ends, which are scalloped, with the centers cast with sunken floral motifs of geometric leaves fanning out. The quillon block is cast with a rosette on both sides, having a raised center dot and four petals formed by a continuous raised ridge. The underside of the guard has an oval stop plate for the scabbard throat. The blade is smooth metal, gray with some dark gray stains, some roughness to the edges in places and a few tiny nicks near the tip, but no significant chips. The one-piece bone grip is very good, with some stains, but not cracks and only some very minute chips at the base of the pommel, which rotates freely around the blade tang, but is secure. The pommel and guard have matching, old brass patinas with a little whitish-green in recesses.

The scabbard is brass-mounted black leather. The leather shows a crease front and back about 7 ½ inches from the top, but is solid and the crease may be from wear or constriction by a cord suspending it in Brownell’s “museum” since we note the frog hook on the upper mount was broken off. The scabbard has wear to the finish, exposing in spots a light brown underneath, on the obverse mostly just above the drag and more generally on the reverse where it would rub against the body. The finish is about 70% on the obverse and perhaps 40% on the reverse, but it should remain as-is. The upper mount is slightly rounded at the bottom edge, 4 ¾ inches long at the center. On the obverse it had a belt hook starting 1 ½ inches below the upper edge, only the base of which remains, but looks like the upper end of the hooks used on regulation Civil War musician and NCO swords. The reverse of the upper mount is crudely, but boldly and deeply engraved: “1st R.I.D.M. 1861” with simple punch dot periods. The letters are made with multiple cuts. There was an effort make both “1s” in the date raised marks in a depressed channel. There is some rubbing to the lighter center lines of the “M.” The boot-style drag is just a hair shy of 6-inches overall with rounded upper edge mirroring the lower edge of the top mount, with narrow side blade and flat tip that is slightly pushed in but bears a short, sharp projecting point. This is engraved on the reverse in crude block capital letters, “KADY.” with a square period. The obverse is engraved “Brownell” in lettering that is also non-professional but somewhat better executed, with block letters for the first six letters and the final “l’s” slightly script.

It is difficult to extract facts from the patriotic, heroic, and romantic legends surrounding Brownell that were read back upon her actual doings. She was renowned as the “Heroine of New Bern” and “Daughter of the Regiment,” a nickname inspired by Donizetti’s popular 1840 opera about a vivandiere, which seems to have melded with the 1860 zouave craze in America. And, it was a role she fulfilled better, or longer, than many rivals in American popular culture, taking part in later theatrical recreations of her exploits, marching in Decoration Day (now Memorial Day) parades, gaining membership in the G.A.R., receiving a government pension, getting newspaper articles written about her, even a poem titled “Daughter of the Regiment” in 1900. Wartime references and reminiscences do, however, support her presence with the 1st Rhode Island Detached Militia in 1861 and the 5th Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry on Roanoke Island and at the Battle of New Bern in 1862. She apparently did carry a flag there, though not the regimental flag or as a regular color-bearer, despite assertions by Frank Moore in “Women of the War” as early as 1866, an account elaborated upon by others, who also gave her a flag at First Bull Run, along with a wound (sometimes serious, sometimes slight- “just a scratch” in her own modest sounding answer to an interviewer.) Subsequent writers mostly followed Moore’s lead and the Brownells were not ones to quibble on details of their patriotic, heroic, and romantic story.

Reportedly born in South Africa in 1842 to a British officer named Southwell (given varied ranks in the retelling) and named after one his comrades, she returned to Britain with her father after her mother died, was placed in the custody of the McKenzie family, and moved with them to the U.S. In 1860 she is on her own as “Kady McKenzie,” working as a weaver in the mills of Providence, R.I., where she fell in love with an iron-moulder named Robert S. Brownell, born 1834. He joined Burnside’s 1st Rhode Island Detached Militia in 1861. The regiment’s adjutant later recalled she had followed her husband to Washington and “called herself a vivandiere and wore a sort of uniform with knee-length skirts . . ,” but asserted she had no official connection with the unit and never heard “that she took part in any battle.” The most romantic accounts not only placed her on the battlefield at Bull Run, but carrying the flag of the regiment’s “carabineer” company, and escaping in the chaos of the retreat to reunite with her husband, whom she feared dead or injured.

After discharge from his three-months service Robert Brownell reenlisted in the 5th Rhode Island and she once again followed him south to be present with Burnside’s forces on Roanoke Island and at the Battle of New Bern, where Robert was seriously wounded in the leg, resulting in his discharge some months later. Frank Moore promoted her to, “a regular color-bearer, but acting in the double capacity of nurse and daughter of the regiment,” and described her running forward under fire in a life-saving act of bravery to wave the flag at another Union regiment in the attack on Fort Thompson and avoid a friendly-fire incident.

A letter written just after the battle by a member of the 8th CT confirms some of this: he had seen her at Roanoke, several times afterward, including slogging along with regiment during the mud march to New Bern with her blanket over her shoulder: “There was one of the officers’ aides riding one horse and leading another one when he came up to where she was. She jumped on to the horse as easy as any man. It was the first time I ever saw a woman ride a horse like a man. In the morning when we got up to start, the regiment formed in the road close by her; she was ahead carrying the flag. She went with them into the battle field and ran some very near chances of being hit, the shell of one bursting close by her side. . . She looks, a little way off, like a young girl of twelve or fourteen years. She was out in the three months campaign. . . There are not many men with more pluck than she has.”

A veteran of 5th Rhode Island provided a few more details: the regiment had no battleflag in the action. One of the men, however, had brought from home a “bunting flag” (i.e. not a silk regimental flag of any sort,) which was given to her, and which carried by the side of the column until they came up to the battlefront and were ordered into action at the “double-quick” leaving her behind. An officer of the regiment recalled that, “just as we were coming under fire of our enemies’s rifles,” she “begged” to carry the flag into the assault and followed orders to go to the rear, “with the greatest reluctance.” She may well have had a close-call with a shell, or waved it to identify the regiment, but Moore and those following him clearly improved the story, which may then have inspired the Bull Run flag episode. (We note Clarke’s history compromises- mentioning the gift to her of a flag to her by citizens in Frederick, MD, on June 18 and her presence on the skirmish line at Bull Run, but not with a flag.) In any case, this flag was likely that mentioned by Moore in 1866 as among her “New Bern trophies” and as exhibited in her museum in the Morris-Jumel Mansion. Moore also played up her tender side as vivandiere and nurse, stressing that she nursed not only her wounded husband, but friend and foe alike. He did admit she tried to bayonet a wounded Confederate, but only after she helped the man and was then viciously threatened in foul language. The 8th CT soldier who saw her there, wrote more succinctly: “She begged the Col. to let her kill one of the wounded rebels to pay for her husband being wounded.”

The Brownells do seem to have been a devoted couple. In an interview they maintained they had never been apart from more than twenty-four hours, and she does seem to have nursed him back to health for months after his wounding at New Bern and he seems to have stayed by her bedside while she lay ill at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in 1913. They were also all-in on the public version of their story, even if they fudged a bit for propriety’s sake. Brownell had been married when they met- since 1853, with several children- and his wife filed for divorce on grounds of adultery- we assume with Kady- in March 1861. His marriage to Kady, variously dated to March 1861 and three different dates in April, thus may not have been legal at the time, if it took place then: their “official” marriage was recorded in November 1863.

In their postwar life Robert worked various jobs. His serious leg wound at New Bern may well have given him trouble. By 1870 they were in Connecticut and she listed herself as an amateur actress, certainly referring to her vivandiere stage appearances. By the mid-1890s they seem to have fallen upon hard times, but Robert got a job with the city and Kady joined the Parks Department, which got her the job as custodian and him as watchman, along with living quarters at the Morris-Jumel Mansion. By January 1913, she was ill. The NY Times described them as destitute with Robert devotedly at her bedside. They apparently resisted initial efforts to get them into residence at the Women’s Relief Corps Home in Oxford, NY, where veterans and spouses could live together, and were removed first to Ward’s Island and then up to Oxford. Authorities seem to have been sympathetic, but the couple had taken over a number of rooms in the house, reportedly even taken in borders, and were at odds with the curator.

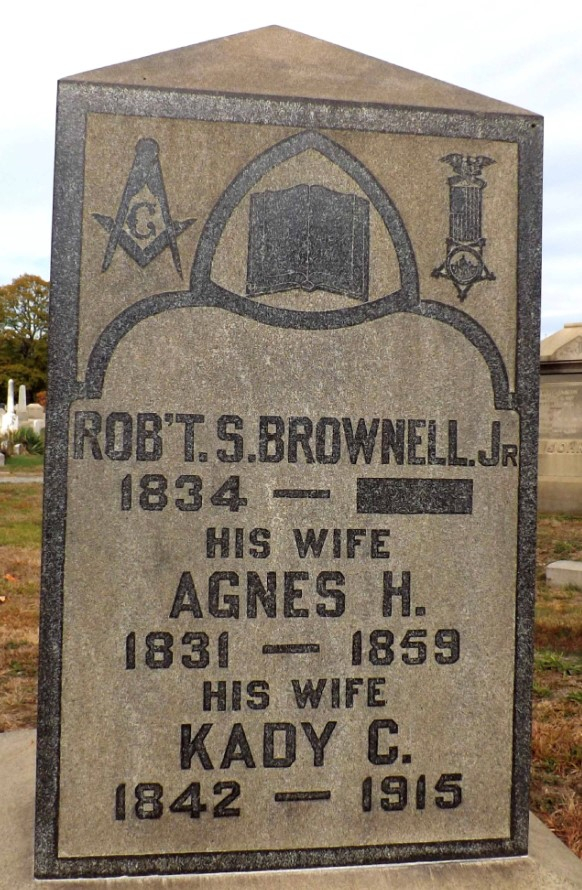

Kady Cottrell Southwell McKenzie Brownell died at the WRC Home in Oxford in January 1915. Robert Brownell reportedly moved to live with relatives in Harrisburg, PA, where died in September, and was buried in an unmarked grave. It is ironic that he did not complete their great romance by being buried beside her back in Providence. He did, however, make one final contribution to their story. He had gathered enough money for a rather large gravestone featuring masonic and G.A.R. badges, with his name at the top, date of birth and blank space for date of death. Below this he had his first wife’s name and dates engraved, with Kady’s name and dates at the bottom- all in keeping with the order of the marriages. The dates for his first wife, however, are both wrong. She was born in 1836, not 1831 (a date making her older than Robert and a more acceptable 21 or 22 rather than 17 when they married,) and her date of death was not 1859: she was alive for the 1860 census and filed for divorce in 1861. Her 1859 date of death, however, legitimizes his relationship with Kady and even their earliest marriage dates. It also lends a bit of pathos to their romance as perhaps consolation for a grieving widower. By that time nobody in Providence was likely the wiser. In fact, Agnes Hutchinson Brownell was not only still alive in 1861, after getting rid of Robert she moved to Iowa in 1867, where she married again in 1868, and died and was interred there in 1914. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

This is a great sword with a wonderful history - public and private. We show a woodcut of Kady Brownell that is probably close to her actual wartime appearance, and one of her later photographs, not in her fanciest garb, but posed with the sword. [sr] [ph:L]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THIS ITEM, AS WITH ALL OTHER ITEMS AVAILABLE ON OUR WEB SITE,

MAY BE PURCHASED THROUGH OUR LAYAWAY PROGRAM.

CLICK HERE FOR OUR POLICIES AND TERMS.

THANK YOU!

Inquire About KADY BROWNELL’S SWORD! “THE HEROINE OF NEWBERN . . . THE COLORS SHE CARRIED SHE STILL KEEPS . . . AND THE SERGEANT SWORD WITH HER NAME CUT ON THE SCABBARD . . .”

Most Popular

Historical Firearms Stolen From The National Civil War Museum In Harrisburg, Pa »

Theft From Gravesite Of Gen. John Reynolds »

Selection Of Unframed Prints By Don Troiani »

Fine Condition Brass Infantry Bugle Insignia »

British Imported, Confederate Used Bayonet »

Scarce New Model 1865 Sharps Still In Percussion Near Factory New »

featured item

ARMED CONFEDERATE LIEUTENANT COLONEL

This uncased eighth-plate tintype is a very clear studio view of a Confederate lieutenant colonel wear frock coat, narrow brim hat, gauntlets and tall boots. He has tilted his hat slightly to one side and wears a sort of tight-lipped smile. His… (1138-2029). Learn More »